Companies that stop communicating their sustainability progress risk setting off a “vicious circle” of corporate non-disclosure and climate inaction, experts worry.

A recent report by South Pole, a climate solutions firm, found that a large percentage of companies that have set net-zero emissions targets have not communicated their goals, potentially for fear of being accused of greenwashing or making exaggerated sustainability claims. This phenomenon is known as green hush.

Speaking at an event hosted by Eco-Business on Tuesday, South Pole’s Asia Pacific head of climate strategies, Shruti Singh, said that green hush makes it harder for investors and consumers to scrutinise the progress companies are making to meet their sustainability targets, weakening accountability.

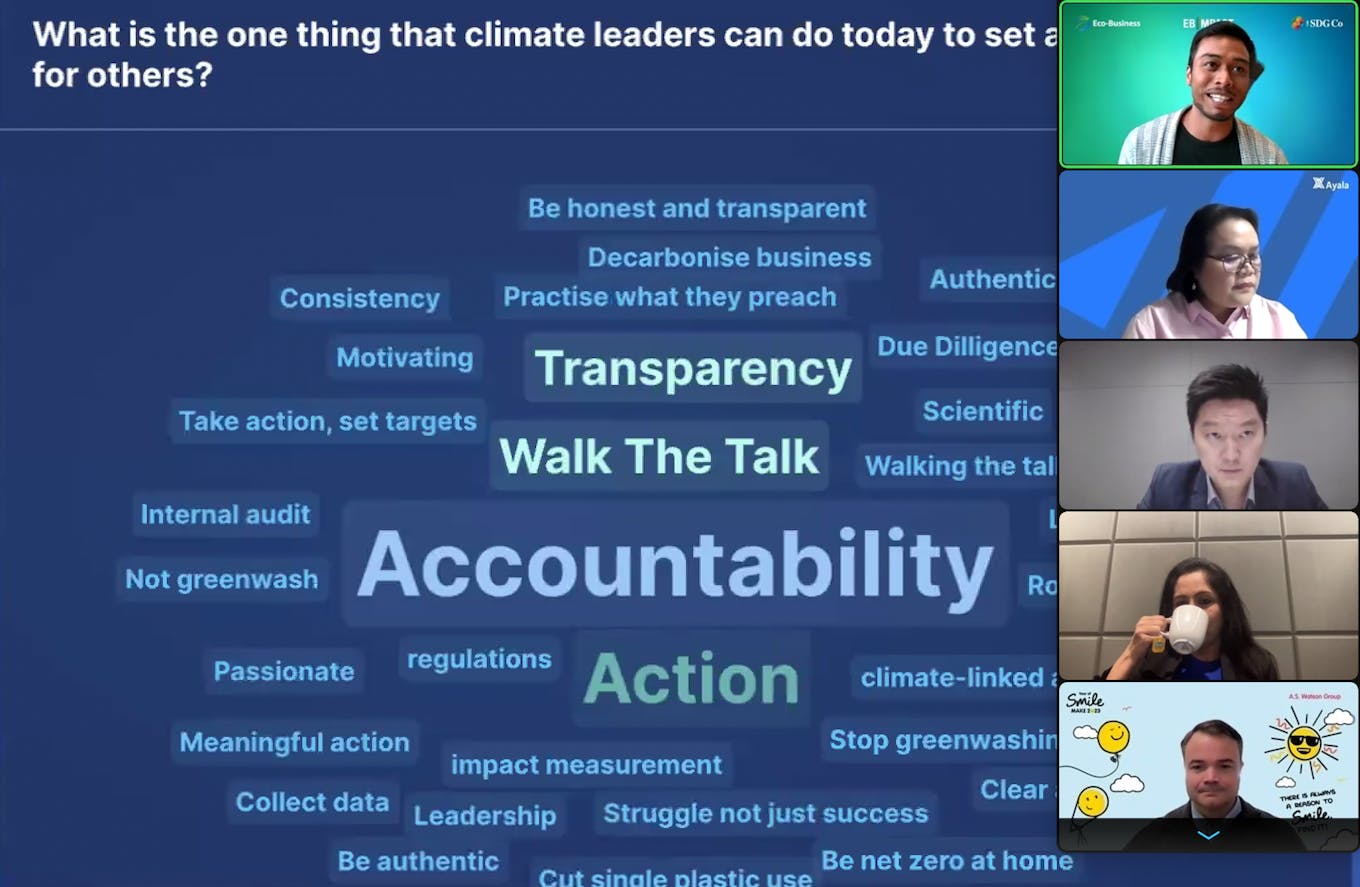

Event participants were asked: What is the one thing that climate leaders can do to set an example for others? Accountability was the main response.

Not communicating sustainability progress also gives a false impression that companies are not taking action, and discourages other firms from setting targets and communicating their own progress, she said.

“Peer pressure” is a strong driver for others to set targets, Singh noted.

“It’s super-important that companies feel comfortable talking about their sustainability journeys – both success and failure,” said Singh, her comments pointing to an emerging phenomenon known as corporate vulnerability – firms sharing the problems they encounter as they work towards sustainability targets in public communications.

“Companies need to overcome this [green-hushing] fear and transparently communicate the targets that they’re setting and the measured progress they’re making,” she said.

South Pole’s report found that green-hushing is happening even as more corporations assign bigger budgets to meet their climate commitments.

However, a June study by Net Zero Tracker, which monitors decarbonisation commitments, pointed to pledges of questionable quality; while more than one-third of the world’s biggest public companies have net zero targets, about two-thirds of them do not yet meet minimum procedural reporting standards.

The study also found that about half of more than 700 corporate net-zero targets are embedded in companies’ corporate strategy documents or annual reports, and most firms have only announced—in some cases only their intention to set—net zero targets.

Leap of faith

Communicating sustainability progress is challenged by the unpredictability of achieving net-zero, and transparency is key, said Victoria Tan, head of group risk management and sustainability for Philippine conglomerate Ayala Corporation.

Tan said her firm’s 2050 net-zero target was a “leap of faith” as achieving it will depend on climate solutions that are “still nascent”. It took the company, whose business interests range from coal plants and manufacturing to automotive and logistics, two years just to set the net-zero target.

“There are issues with Scope 3, because of lack of data,” she said, referring to the company’s value chain emissions. Scope 3 emissions are notoriously difficult to measure but make up the lion’s share of indirect corporate emissions, according to CDP, a carbon measurement non-profit.

Variation in Scope 3 data has meant “a lot of recalibration” of the company’s emissions baseline, but these changes have always been communicated with investors, Tan said.

“We want to learn from the failures, because every failure is an opportunity to improve internally and improve our processes as well,” she said.

In an interview with Eco-Business in October, Cherie Tan, a former Unilever executive who now leads Asia-Pacific sustainability for agrochemicals firm Bayer Crop Science, said that there is too much communication from companies around commitments and not enough on implementation.

More transparency around the challenges of implementing green goals could pave the way for more credible sustainability communications and result in fewer allegations of greenwashing, she said.

Tan Szue Hann, head of sustainability and deputy general manager of Sustainable Urban Renewal for Singaporean property development firm Keppel Land, said that companies were “damned if they do, damned if they don’t” with sustainability communications, and said firms should not “over-promise” and be authentic.

Keppel Land is aiming to halve its direct and indirect emissions by 2025, and achieve net-zero by 2030.

It’s been a big year for companies called out for greenwashing, with firms running into legal trouble for making misleading sustainability claims for the first time.