It’s not often you get a Nationals MP berating Labor for going too slow on the green energy transition. The party and its MPs have been obsessed in recent months with trying to stop the transition in its tracks, and urging the country to wait for a nuclear unicorn in the form of small modular reactors.

But Adam Marshall, the NSW state member for the Northern Tablelands, which overlaps the federal New England electorate of anti-renewable agitator Barnaby Joyce, had some telling observations to make this week when the state Labor government released its new draft guidelines on wind energy.

The renewable energy industry has been stunned by the guidelines, which unless changed will effectively say no to wind farms in most parts of the state, particularly in the renewable energy zones that were designed specifically to accommodate them.

It’s an important issue: NSW is the biggest economy, with the biggest population in the country, and has the biggest grid, the biggest coal fleet and is the biggest importer of energy. What happens in NSW is important to the rest of the country, and the federal Labor government’s own ambitions for renewable and emission cuts.

Marshall, a former state parliamentary secretary for renewable energy, noted the massive contradiction of having the energy department scampering to keep up with the energy transition and the need to build new wind, solar and storage to replace coal, and the planning department erecting massive barriers.

“We now effectively have two government departments saying two completely contradictory things about the future of our region,” Marshall wrote on his web site.

“It’s not only embarrassingly amateurish, but also very concerning for our community.”

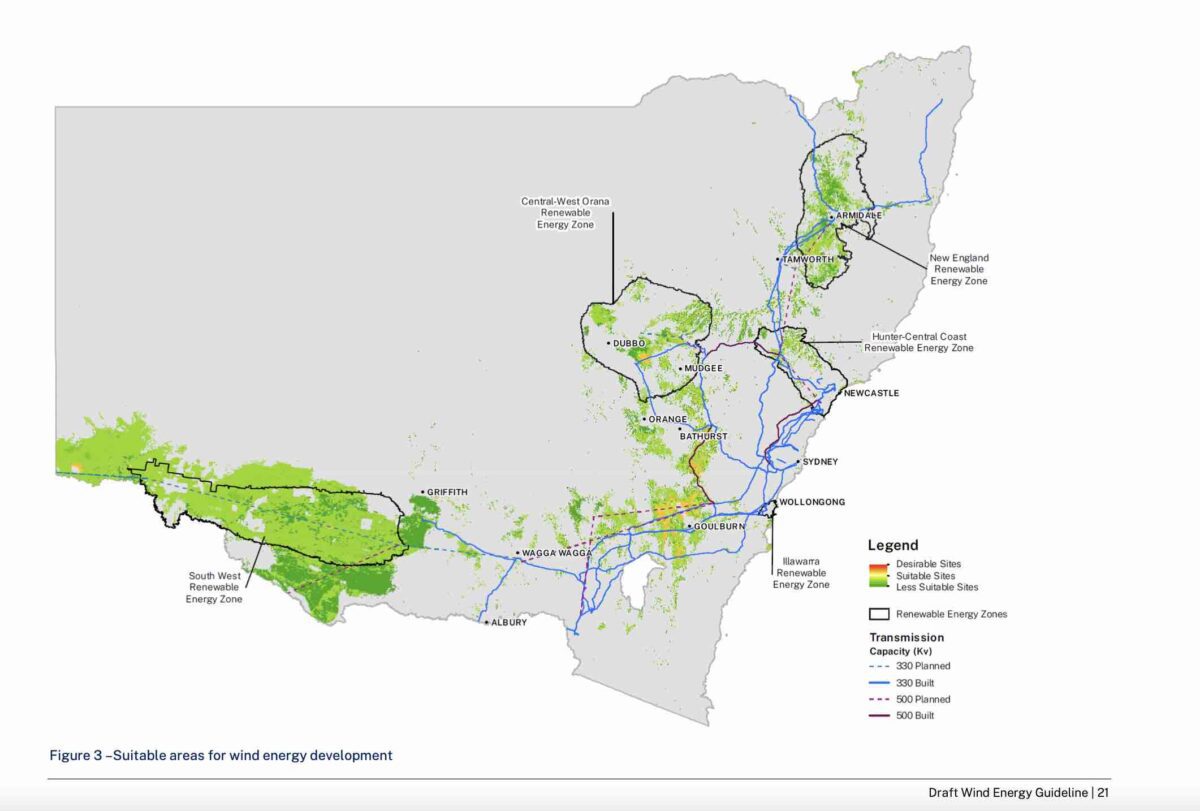

Marshall noted that the new map published in the draft guidelines (see above) declares almost the entirety of the New England REZ as “less suitable” for wind projects.

“The Planning Department declares us ‘less suitable’ for wind projects while at the same time the government’s Energy Corporation is working to expend hundreds of millions of taxpayers’ dollars constructing new high voltage transmission lines across our region for new projects to connect to,” Marshall wrote.

“Who is correct; the planning department or Energy Co? Because they cannot both be right. Will there be no new wind projects approved in our region, or has the planning department got it all wrong and doesn’t have a clue what’s going on in the government?

“Threading the needle to ensure a smooth energy transition, developing new renewables in harmony with our local communities, is difficult enough without this sort of carry on which shatters any confidence we had in the key government agencies.

“Either we have renewable energy zones where these projects are supposed to go or we have a planning system that is now attempting to rule them all out – we cannot have both and this government needs to work out what it’s doing and fast.”

To be sure, Marshall is playing politics for all he’s worth, and has shown an uncanny ability to straddle the barbed wire fence between climate science, energy reality and Nationals ideology, and RenewEconomy is not in the habit of giving Nationals MPs such a big free kick.

But it is worth highlighting those comments because – as RenewEconomy has discovered in its conversations with a number of senior players in the renewable energy sector – they reflect exactly what the industry thinks right now.

For its part, the NSW energy department is at pains to insist that these are draft guidelines, and can be changed.

But the reality is that the biggest problem – the new 2km setback imposed on wind farms from even a proposed “dwelling” in a neighbouring property – has been around for a long time and is already influencing planning decisions and causing wind projects to be amended or withdrawn.

These rules – draft or real – allow for opponents to simply pay a modest sum to get a quick “planning approval” for a building on property boundaries they may have no intention of building or living in. It is enough, under these rules, to force a wind project to be massively redrawn or abandoned.

Renewable energy advocates say they have been discussing the issue with the Labor government since soon after its election in March this year, and had detailed meetings in May. But to no avail.

“There has been no change since then, no change in behaviour,” said one industry insider, who – like others – asked not to be named because of the sensitivity of the issue.

“And we haven’t seen another wind farm approved.”

The renewable industry says it has respect for energy minister Penny Sharpe. “She listens,” is a common observation, and the industry believes she is across the issues.

But despite her seniority in the NSW Labor Party – she leads the government in the Legislative Council – she appears not to have the carry-through of her Coalition predecessor Matt Kean, because she appears not to have the active support of premier Chris Minns or Treasurer Daniel Mookhey.

Industry insiders say neither Minns nor Mookhey appear particularly engaged with or informed about the energy transition, which makes it difficult for Sharpe to overcome the inertia from the office of planning minister Paul Scully, who one insider described as “absent.” “He wants to pretend it’s not happening,” observed another.

Kean had the advantage of having the office of treasurer too, and the ear of then premier Dom Perrottet, which meant he was more able to overcome the inertia from the Coalition’s own planning minister, Anthony Roberts, a former state energy minister who showed no interest in hastening the transition.

Kean was admired for his vision and his determination, and his ability to bring others – particularly the Nationals – on board. Not everyone was convinced by the details of his renewable infrastructure roadmap, but at least he had a credible plan, and ambition.

The legacy of those plans, as we feared at the time of the election, now risk being trashed because Labor can’t get its act together on its promise to follow through. It had given bipartisan support to the Kean roadmap.

The contrast with Western Australia, for instance, is sharp. That state had a sudden awakening when its big industries made it clear to the government that they wanted, and needed, green energy if they were to remain competitive in international markets – both in terms of price and emissions.

That state, long a laggard in the uptake of renewables, is now fast tracking a plan to have more than 50 GW of new wind and solar capacity installed in the next 20 years, and is removing obstacles in the way of that plan, rather than erecting them.

The stakes are now getting high – climate impacts are becoming more obvious, temperatures on both land and sea are rising faster than expected, and the state’s ageing and increasingly unreliable coal fleet can’t be counted on in the extreme temperatures expected in the forthcoming El Nino summer, and those that follow.

Other areas of tension are also emerging in NSW, including fears of friction between EnergyCo, the state body created to manage the renewable energy zones and new transmission lines, and AEMO Services, the body charged with managing a series of auctions for new generation and storage.

Important auctions such as access rights for the renewable energy zones – effectively a payment to secure a spot on the grid and not be heavily constrained – have been delayed.

And the paucity of new projects in the pipeline is reflected in the generation auctions, where underwriting deals have gone to projects already being built. A similar result is expected for the next auction due to be released in coming weeks.

Some aspects are going well. Households are investing in rooftop solar, and large scale battery storage is being built across the state.

The most visible of these is the Waratah Super Battery, which will be the biggest in the country and act as a kind of giant shock absorber for the grid, allowing transmission lines to be loaded with greater capacity to deliver power to those that need it.

The results should also be known soon of the first auction under the new federal Capacity Investment Scheme, looking for 930MW of two-hour storage (likely more big batteries) in NSW to help fill a gap identified by the market operator should the Eraring generator close, as currently scheduled in August, 2025.

But the growing fear is that the NSW government may find itself with no choice but to pay Origin Energy big amounts to keep at least two of its units open for another couple of years.

Origin has played its cards well, earning brownie points for announcing an early closure of Eraring – which some suspect is partially forced by issues with its dam that is reaching capacity.

But, like other big utilities, Origin has done little to replace that lost capacity, so now finds itself dealing with supplications from a state government fearful of the lights going out and/or electricity prices jumping.

What the state needs as much as anything is a lot of new generation capacity. And most of all, to balance out the impact of rooftop and utility-scale solar in the middle of the day, it needs more wind.

But, as Marshall might observe, the NSW government is not giving any indication it is opening the door to wind energy any more than Barnaby Joyce. What the state really needs now is strong leadership.

See also: Renewables and farmers: Is this golden opportunity about to slip through our fingers?