For AGL investors considering the AGL demerger, it is clear that splitting the business in two will increase the value of at least the retail business, AGL Australia (AGLA).

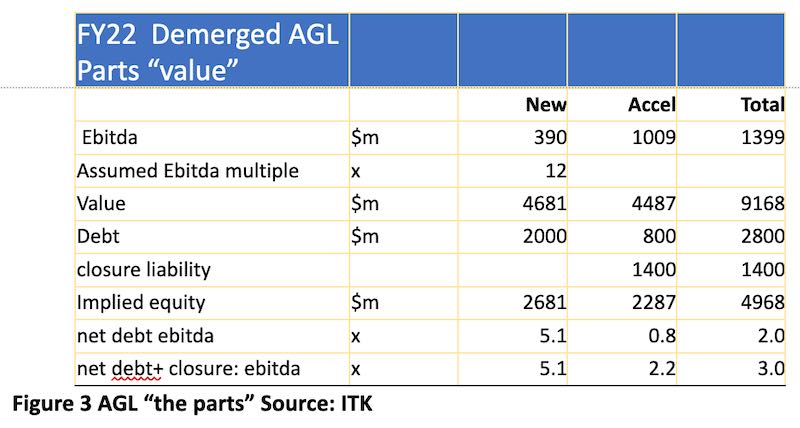

The issue is that AGLA earnings (proforma ebitda) in 2022 of $390 million are less than half the size of the coal generation business, Accel (whose proforma 2022 ebitda was $1,009 million). So, the question completely turns on the post-demerger equity price of Accel.

Our view is that the demerger obviously increases the risks to Accel’s future by isolating it away from its retail captive client.

Equally, even putting specific carbon risks to one side, there are a whole bunch of revenue and cost issues in front of Accel that won’t be reflected in the FY2023 numbers that investors will probably use to evaluate the demerger.

AGL management say they expect AGL to earn around $1,400 million of earnings before interest tax and depreciation [EBITDA] in FY22. The ebitda is a proxy for cash flow. The cash flow is used to pay tax, pay capital providers (debt interest and equity dividends) and to reinvest in the business.

The multiple reflects the market’s opinion of risk and return in comparison to other investments. Where buy and sell valuations agree is where the price is set.

AGL has an ebitda multiple of about 6.5x which for a large company, when interest rates are low, is a very low multiple. A whole bunch of US utilities trade on 15x EV:Ebitda.

We have allowed for Accel’s coal closure liability. The liability “value” measured as the net present value of the closure costs is estimated by management in 2022 at $1.4 billion.

It’s a long discussion as to whether this is the “right” number, and if you are an optimist you can say the sites will be repurposed and the liability deferred indefinitely. Still, investors that wish to avoid being caught with their pants down will likely just accept the estimate

The ebitda of $1400 million is the top end of management guidance.

Management split the FY22 ebitda up between coal [Accel] and the rest of AGL Australia [AGLA]. However they haven’t yet indicated what the “head office” overhead split between the two businesses will be, or indeed how the functions will be split up, or what costs will be incurred after the split by each of the businesses.

Nevertheless, an approximate split might look something like as follows:

Most of the earnings right now come from Accel, the coal generation business.

We know that, initially, AGLA will have about $2,000 million of debt and Accel will have about $800 million.

We can confidently expect that AGLA will sell for a higher ebitda multiple than the old combined business. We expect that for three reasons.

- The old combined business is very low by market average and so almost any new business will sell for more;

- Comparable utilities around the world that don’t have much coal or gas generation sell for over 10x ebitda;

- Large customer bases are scarce assets and well valued by the corporates.

Generally speaking, we think investors would anticipate AGLA would sell for at least 10x ebitda, but we are going to push and use 12x or $4,681 million in total. We use 12x to reflect our optimistic view of per-household growth.

If AGLA is worth $4,681 million and the existing undemerged business is valued at $7,768 million then, by subtraction, if Accel is valued at about $4.5 billion gross, or has an equity value greater than say $2.3 billion, then investors are no worse off by the demerger.

After adjusting for the allocated debt, the equity values would then be relatively close.

We struggle to see how ACCEL can be worth $4.5 bn

If we only look at Accel’s cash flows out to 2030, we estimate a value, net of the debt and closure liability, of about $1.7 billion.

Despite a long background in estimating profits and cash flows I have low confidence in my projections. Frankly, with supply moving around, prices going up and down, costs shifting, there is room for a range of values.

The general point to be made is that if these numbers are even roughly appropriate, Accel’s post-2030 coal gen operations would need to have a value today of over $1 billion to make the merger seem like a good idea. That is not impossible, but I personally don’t see much upside to it.

Value of ACCEL at time of AGL acquisition about $4.8 billion

To put these numbers in context, the acquisition prices for LYA and Bayswater/Liddell in 2012 and 2014 added up to over $4.5 billion.

ITK thinks that AGL management and its advisor Macquarie Bank played investors for total fools in those acquisitions.

Most egregiously, management did not disclose the Ebitda for either business to investors. Neither was the closure liability acquired disclosed (assuming management actually thought about it). Still, if professional fund managers were prepared to invest billions of dollars without adequate information, who are we to argue?

The LYA ebitda for 2012 is a 10 year old memory of what was an estimate at the time and could be way out.

ACCEL discussion

A nine-row summary of our Accel cash flow model to 2030 is shown below:

Accel faces a range of well known, and less well known, problems, most of which won’t be that visible in FY23, the year on which the demerger numbers will be based. Those issues, as ITK sees them, are:

- Accel contracted and captive volumes decline from 85% of output today to potentially less than 15% of output by 2028. New contracts could (will) of course be written.

- Fixed costs increase steadily at LYA and in NSW Accel’s coal cost advantage will be gone in, at most, five years.

- Ongoing new supply of largely wind and solar energy will by 2028-2030 have easily offset the impact of coal generation closures announced today.

- There are ever present residual risks of external carbon costs being imposed.

- Electricity futures and ITK analysis point to higher prices in NSW for the next three years until new supply starts to really impact, but there is no real improvement forecast in Victoria.

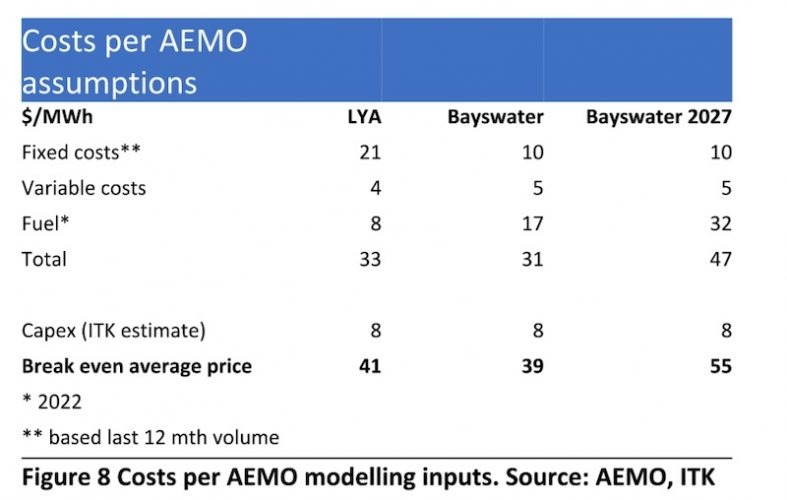

- Liddell is closing in FY24. That reduces Accel’s volume by 8TWh. If we use AEMO’s cost numbers Liddell’s average cost works to about $32/MWh and, using a pool price of even $70/MWh, then the margin is (70-31 = 49). For 8TWh, on that basis that’s a loss of $392 million margin. I suspect Liddell costs are higher than assumed for AEMO modelling and capex also falls, but there will be quite a decent earnings fall.

It’s easy to be too negative and AGL management decided to close Liddell in full knowledge of the profits the plant earns, as did Origin with Eraring for that matter. But the broad point remains that just focusing on the fact that NSW power prices have gone up for the next couple of years and Eraring is closing isn’t enough necessarily to hold Accel’s earnings, even at the depressed FY22 level of $1 billion.

AGL has plans to repurpose its sites when they do eventually close into “energy hubs,” but in ITK’s opinion the price that investors would pay for the “hub option” is low compared to the $1.4 billion closure liability. And, in fact, the supply of “energy hubs” is likely to be larger than demand, given the number of coal plants to close.

We anticipate that for those reasons investors are likely to take a conservative attitude to Accel. In this note we mostly ignore ESG considerations, except to say that in the end they are the most important issue in the medium term and, specifically, that they act to make it difficult for Accel investors to exit the stock.

Revenue

In 2021 we see the demand and supply for the coal generation assets as:

85% of current volume is related to New AGL and aluminum. Both are under threat.

ITK believes that Rio wants to green its assets and aluminum will be a big part of that.

ITK thinks that there is zero reason to demerge AGLA from Accel if AGL Australia is going to keep buying coal generated electricity from Accel. Investors would see right through any such artifice.

By this logic AGLA is, within five years, going to stop buying from Accel and by the same logic it’s going to cause new supply to be procured to replace ACCEL, and that is going to be lost volume for some thermal supplier.

The annual flat load prices used in the estimates are shown in the chart below. Note that the received prices reflect a three-year trailing average and a separate price for aluminum loads. We have assumed that, out to 2030, expiring contracts can mostly be replaced with new contracts. However we model the certain loss of 8TWh of Liddell volume.

We think that from 2028, both LYA and Bayswater will be struggling to sell all capacity but nevertheless maintain NSW volume but allow LYA to fall off 3TWh. This assumption does impact valuation materially.

2.2 Costs

Primarily, we use the AEMO estimates, although they are informed by other sources, including the company presentations.

Using the AEMO input worksheet, we note estimated costs as follows:

Fixed costs are input as $/kW of capacity, but we have converted them to $/MWh based on expected output.

2.2.1 Coal costs

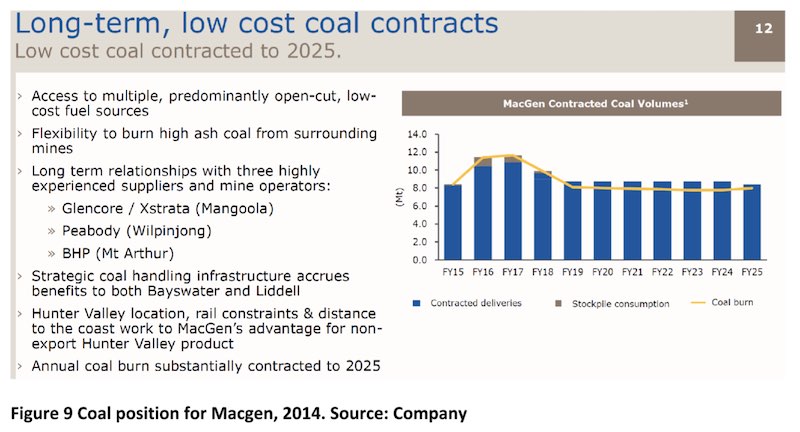

AGL noted at the time of Macgen acquisition stated coal was contracted to 2025:

AEMO assumptions increase the Bayswater coal cost from $1.8/GJ to $3.25/GJ but not until about 2029. We have adopted the AEMO model, but see the risk is earlier cost increase. We have long thought the Liddell closure partly relates to maintaining low cost coal for as long as possible.

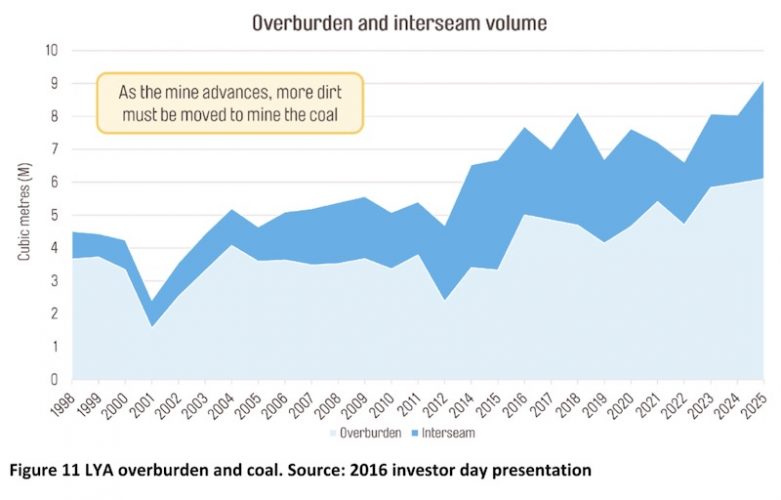

2.2.2 LYA costs

The issue with LYA relates to (1) The mine moves away from the power station about 100 metres every year, but actually at some point turns around and goes back toward the station; (2) Generally there is more overburden removed; (3) An ageing work force has lead to high-ish labour costs. Management stated at the 2019 investor day that LYA costs were expected to be stable and we have modelled only inflationary style increases.

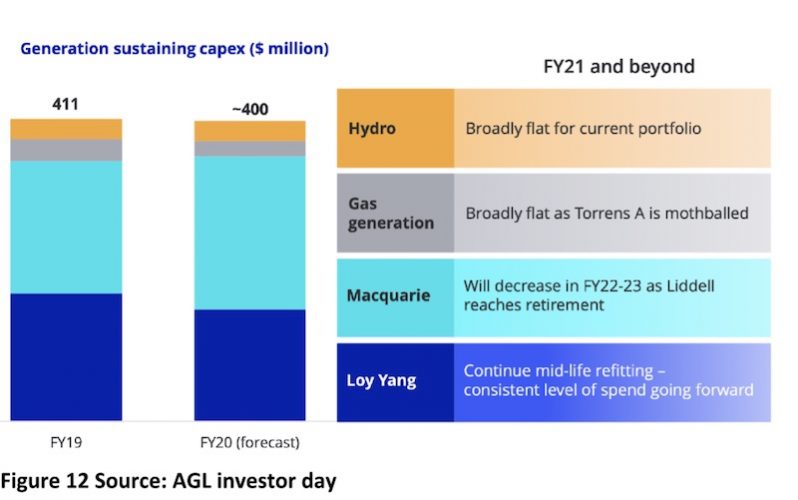

2.2.3 Capex

ITK has modelled a steady and sharp reduction in capex over the next 10 years. Capex is inherently difficult to model without management information. Capex can often be deferred but eventually has to be incurred.

AGL has been spending about $300 m a year on capex. Based on management statements and recent history, in our opinion it is more likely that sustaining capex will be higher than we have allowed, rather than less. Our declining forecast is based on a view that a shorter life for the assets will lead to less capex. Management have different plans.

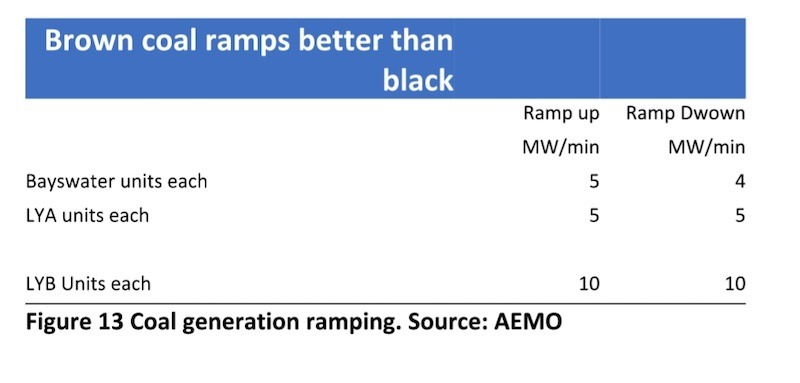

One reason to keep spending capex is to improve ramping flexibility, where AGL is behind Alinta.

3. AGL demerger is more difficult than most

ITK initially supported the AGL demerger on the basis that AGL had to do something, it was becoming un-investable due to carbon risk.

The demerger offered a way to separate out the “good” business from the “bad” business. Typically, demergers do create value, even if on paper they shouldn’t.

Investors with long memories might remember the largest utility in the Australian market today, APA was spun out or demerged from AGL. Origin was spun out or demerged from Boral less than 20 years ago. A lot of value has been created by demergers.

However since the demerger was first proposed, the outlook for coal generation in the NEM has become significantly worse. That’s because the closure of Eraring and Victoria’s commitment to offshore wind will result in even more variable renewable energy [VRE] being introduced earlier rather than later.

Additionally the fact that the industry consensus judgement that the NEM is on a “step change” trajectory will reinforce in both policy making and industry setting the need to be ready for the post coal generation world.

Of course the transition will be bungled, of course there will be problems, but there is little pushback against the direction or the speed. The federal government has become irrelevant, its views ignored by all and sundry. Nature, after all, does abhor a vacuum – and what a vacuum federal policy has been.

Many in the coal generation world will have seen opportunity in the Eraring early closure, which together with the already announced closures of Yallourn and Liddell have already reduced coal generation capacity materially.

In terms of MW about 28% of capacity is to be closed, in terms of annual energy it’s less but I doubt if there are any informed stakeholders that think Eraring will be the end of it.

Queensland can’t meet its VRET without doing something, and has pretty much signalled, in my mind anyway, that Gladstone – at a minimum – is going.

Notwithstanding that average prices for coal generation may be perfectly adequate to cover costs per MWh it’s the total annual revenue and costs that drive the business. And it’s from that perspective that we look at the outlook for Accell.

3.1 Losing captive volumes clearly increases risk and cost of capital

Accel’s revenue outlook will be much more uncertain after the demerger than before.

Before the demerger, Accel had a captive client: the retail business. After the demerger, it only has a five-year declining balance contract and one that faces a very good chance of not being renewed. After all, weaning AGL Australia off coal generation is the demerger rationale.

On top of that, whether Accel was demerged or not, there is every likelihood of Tomago not renewing its current contract post 2028.

In our view, although not totally obvious to all, Rio has made a fairly clear signal under new management it wants to decarbonise its aluminum assets .

And, in our view, and it is contested, there is a clear path to a firmed renewable energy supply for an aluminium smelter that is lower cost than competing coal fuelled aluminium in, say, China, and lower cost than a new and increasingly uncertain coal generation contract in NSW.