The federal Labor government’s proposal for “timid” and “weak” changes to the Petroleum Resource Rent Tax should be dumped and replaced with a plan for a Norway style sovereign wealth fund.

The calls follow news that the federal government has opted for a recommendation from Treasury which will see a cap imposed on deductions that oil and gas companies are allowed to use to offset the amount of PRRT tax they pay.

Instead of being allowed to use credits from previous spending to offset tax, from 1 July this year that will be capped at 90 per cent, meaning a company will always have to pay PRRT on at least 10 per cent of income from a project.

This comes with a seven-year grace period, however: from the date a project starts it has seven years of no cap in order to recoup its costs.

Indepent MP Sophie Scamps says the initial reforms, which will deliver just $600 million a year extra to the PRRT, are a “positive first step”, but she is calling for a complete redesign of the PRRT.

“If Australia taxed oil and gas exporters in a similar way to Norway, we could add billions of dollars to the budget each year and it would benefit us all,” she said in a statement.

“Nearly 30 years ago, Norway implemented a simple 55 per cent special tax on their resource profits on top of the corporate tax.

“They also tightened up their laws on transfer pricing. As a result Norway now has a sovereign wealth worth over two trillion dollars for the benefit of future generations. In contrast, Australia is leaving future generations a massive debt of nearly $1 trillion.”

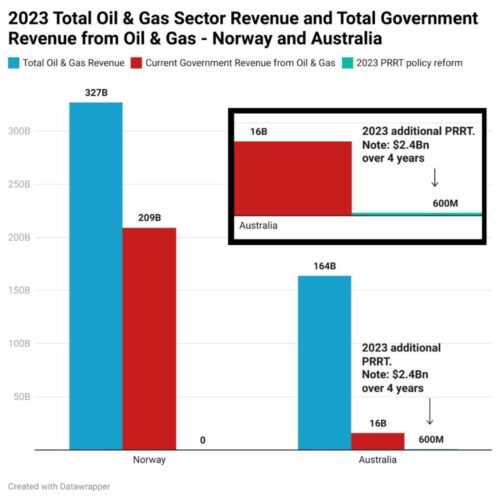

In 2023 alone, Norwegians’ share of the country’s oil and gas sector will amount to $209 billion, a 63 per cent cut of the industry’s revenue.

In Australia, however, the publics’ share will be not quite 10 per cent, according to data collated by TheDriven lead reporter Daniel Bleakley for The Australia Institute last year and published in MichaelWest Media.

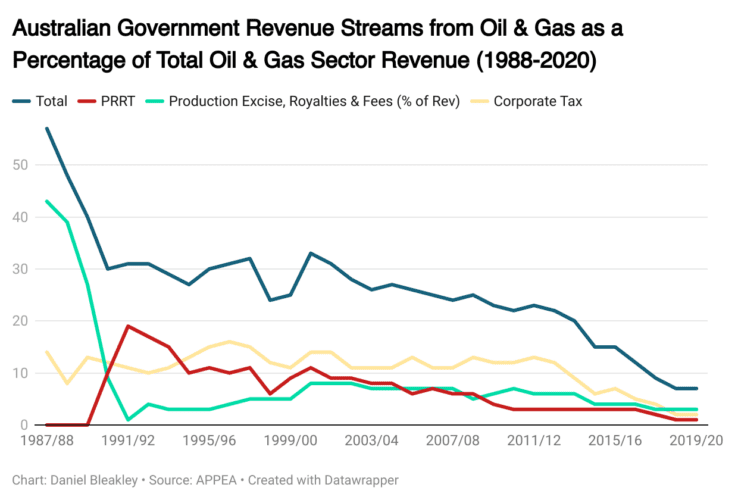

The PRRT was created by the Hawke Labor government in the late 1980s to tax oil extraction, with a 40 per cent tax and a 30 per cent company income tax totalling, theoretically, 58 per cent.

But as the industry has moved to gas it’s proved ineffective at actually raising any money.

In the 2021-22 financial year, the PRRT generated a record low $900 million and continues to deliver only a circa-1 percent royalty on offshore oil and gas for Australia — despite $11 billion spent in fossil fuel subsidies.

A Greens’ plan, proposed at the federal election in 2022, wants to cancel the carried-forward tax credits and end the uplift factor — a PRRT detail that allows carried-forward credits to rise up 5-15 per cent over the long-term bond rate.

It’s resulted in gas company tax credits ballooning to $284 billion, the Greens say, or 1.7 times what the industry says it will make in 2023.

The Greens would apply a 10 per cent royalty to all offshore projects that are subject to the PRRT, to create a separate, baseline level of annual revenue, deductible against the tax.

The total value would be an extra $94.5 billion in revenue over the next 10 years, compared to the federal Labor plan which will deliver an estimated $2.4 billion over four years, the Greens say.

Transfer pricing tinkering won’t work

The Treasury Treasury Gas Transfer Pricing (GTP) Review report into the PRRT, which was commissioned by the former Coalition government, made 12 recommendations for reforms and three ways to overhaul the payments structure.

The alternatives to a deduction cap revolved around tinkering with transfer pricing, a method that sees gas taxed at a lower price before it goes through the value-adding process of liquefaction.

The Treasury report said the amount of expenses companies can deduct, plus that fact they can also deduct expenses associated with liquefaction and shipping — after the PRRT is charged — means some companies never pay tax at all.

Reforming just transfer pricing won’t prevent this.

The Norway model removes this problem with a tax on exports only with a 55 per cent resource tax and a 22 per cent corporate tax. The country ended royalty payments in 2005. Stronger tax avoidance laws also mean actions like Chevron’s, which used shell companies in different jurisdictions to shift profits offshore, aren’t possible.

Over 2021-2010, the Norwegian oil and gas revenue pot was divided 55 per cent to the government, 21 per cent on expenses, and 24 per cent as private sector revenue.

In Australia, expenses swallowed 90 per cent of all oil and gas revenue, thanks to company-reported expenses associated with the cost of extracting, liquifying and shipping LNG.

However, companies’ own reports of their expenses do not tally with those reported to the Australian Tax Office.

In its 2021 full year briefing, Woodside reported total expenses of 55 per cent — not 90 per cent — including production and other costs, and depreciation and amortisation. Its expenses have been around this mark for the last five years.