The Australian wind industry has again expressed concern about NSW planning rules that they say will allow vexatious objectors to stymie new developments by lodging plans for dwellings on the edge of properties that they might never build.

The concerns over the rules have been running for some time, and are confirmed with the release of the planning decision process for one of the state’s most hotly contest wind projects, the Hills of Gold wind farm near Nundle, south of Tamworth in the New England region of NSW.

The Hills of Gold wind project was originally put forward as a 95-turbine facility, before starting the formal planning process with a proposal to install 65 turbines with a total capacity of around 420 MW. Last month, it finally won approval from the state planning department after being pared back to 47 turbines with a combined capacity of 295 MW.

But it is what has happened in the planning process, and why, that has disturbed the industry. The owner and developer of the project is Engie, which is not commenting because the project is still subject to review and approval from the Independent Planning Commission.

But the industry has seized upon the revelations of the state planning documents as a sign of the problems that can face wind farms in NSW, where just a single wind farm has gained planning approval in the last four years.

“The proposed NSW wind farm guidelines cement the ability of neighbours to “strategically” propose a house (even when they have no intention to build) on their property to eliminate nearby wind turbines,” says a development manager with one major renewable energy devbelopment com pany.

“This results in vexatious neighbours becoming potential project killers.”

He cites the example of the state’s requirement that 11 wind turbines be deleted from the Hills of Gold wind farm development, because of “one hypothetical house, that may, sometime, but probably never, be built.”

The planning documents published on the DPE website confirm that one property adjacent to the proposed wind farm submitted a plan to build a dwelling on the edge of their property in August, 2018 – two months before the Hills of Gold scoping report was filed in October, 2018.

The neighbour’s application for a single story dwelling was refused by the Tamworth Regional Council in late 2019, the DPE document notes, but the neighbour then obtained a “complying development certificate (CDC)” in late 2020 for a dwelling just 330 metres from the closest turbine in the proposed project.

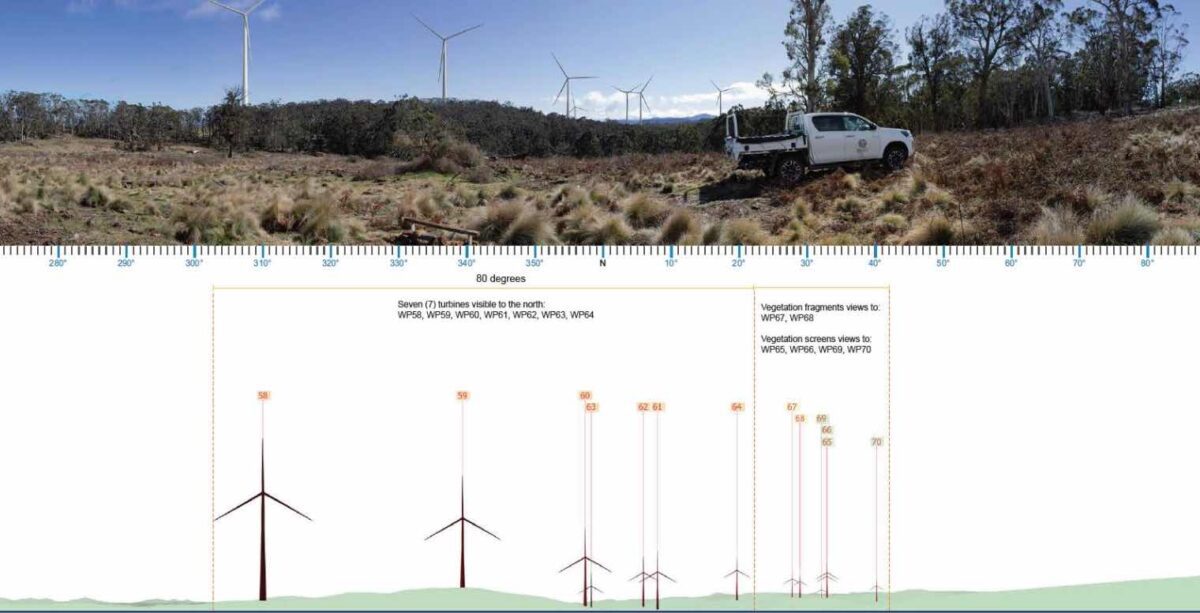

The DPE said it usually provided less weight to the impact on potential future dwellings than existing dwellings. But in this case, it said, because of the “steep topography”, the close proximity of six turbines within a kilometre of the proposed dwelling, and the inability to mitigate these impacts with vegetation, it found in favour of the neighbour.

“The Department recommends deleting 11 turbines (T53 T63) which it considers would sufficiently alleviate visual (and noise) impacts at DAD01 (the proposed dwelling),” it wrote. It refused an application from the developer to seek to buy back the affected land.

“While the project as proposed would contribute towards the significant transition of the grid needed to achieve NSW Government targets of reducing emissions by 70% below 2005 levels by 2035, removing 11 turbines would not jeopardise this transition,” the DPE writes.

The wind development industry is not so sure.

“When it comes to renewables, governments need to stop doing dumb things,” said John Grimes, the CEO of the Smart Energy Council.

“The draft NSW Wind Farm Guidelines simply do not prioritise climate action. In too many circumstances thy make it harder – not easier – to develop wind farm projects.

“The idea that a hypothetical home could disrupt a wind farm project is just one example.

“What this means is that one person’s ‘right’ to (potentially, but very unlikely) build a dwelling vexatiously positioned on their boundary next to the proposed wind farm is more important than a $100 million investment and more than 35,000 people having access to clean, cheap power”.

It is not the only time that proposed dwellings have become an issue. They were raised in the planning process of the newly approved Glanmire solar and battery project, where a near neighbour wanted to sub divide into four residential lots.

However, with solar the visual amenity and noise issues are less of a problem, and can be more easily addressed with screening. It did not interfere with the development of that solar project, although setbacks were increased.

For wind, however, it is a different matter. And there have been numerous concerns expressed about the draft planning guidelines, particularly how they affect wind farms, which add to concerns about higher fees and other issues.

The Clean Energy Investment Group last week urged the NSW government to deem more projects as state significant infrastructure.

It raised fears that the new draft guidelines are likely to create more delays, add more costs, and introduce more layers of bureaucracy.

It cited the new draft visual impact guidelines, which it says are not based on evidence and exaggerate the visual impact of wind turbines on dwellings, and require more consultation with the likes of landscape architects to give a better assessment of what visual impacts should look like and how it should be managed.

CEIG believes the assessment requirements should be more flexible and says they don’t offer enough guidelines for addressing moderate visual impacts.