When Australia’s quarterly emissions are released, I usually throw out a few social media posts, but the latest batch takes the data up to the end of 2023, so that feels worthy of an article.

I run a file that tracks both the emissions and revisions to the data on emissions, creating a ‘version’ of each new report. And the latest batch reveals a bunch of important things.

Australia’s emissions aren’t falling anymore

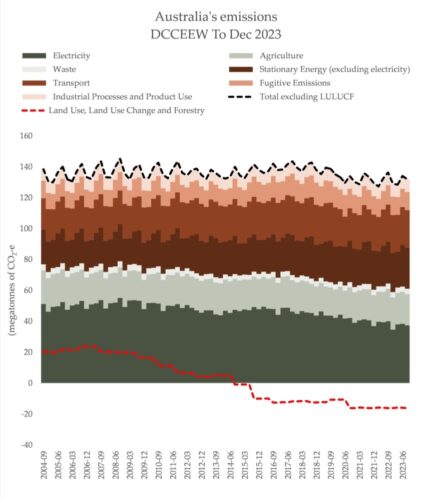

For a couple of years now, Australia’s total emissions have essentially stopped falling. While the power sector continues to (slowly – more on that later) fall, heavy industry, transport and agriculture are rising. The net result:

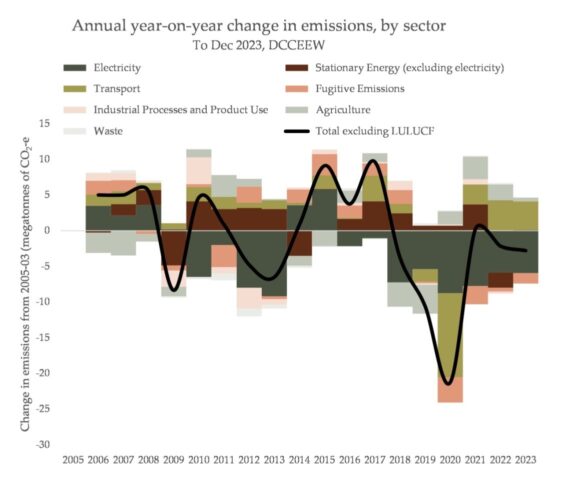

You can see this tug of war, heavily skewed by COVID, represented nicely when you visualise the year-on-year change in each sector:

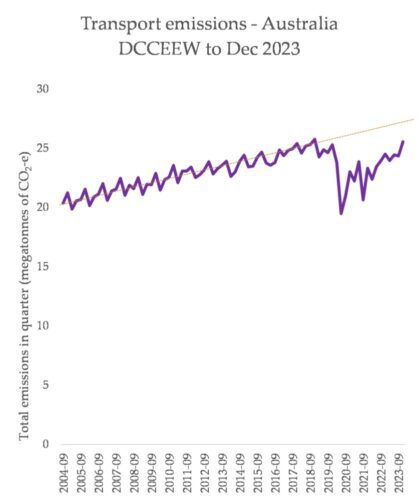

Rebounding agriculture and transport in particular are cancelling out reductions in the power sector. Australia’s transport emissions will be back to pre-COVID levels pretty soon:

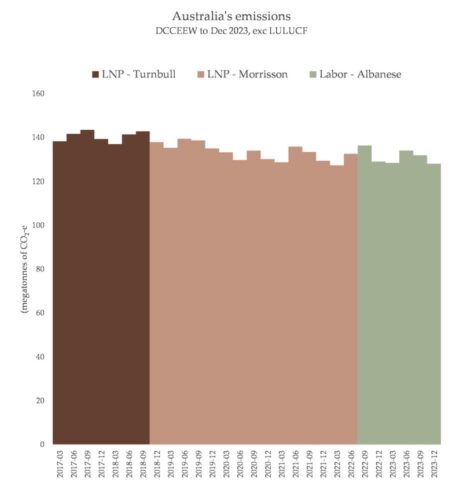

It’s worth noting that the Albanese Labor government has seen six quarters of emissions data – that’s 40% of the tenure of the Liberal/National Scott Morrison government. It is a long time they’ve been in charge now, and I think that it’s time to start scrutinising their record in dealing with emissions.

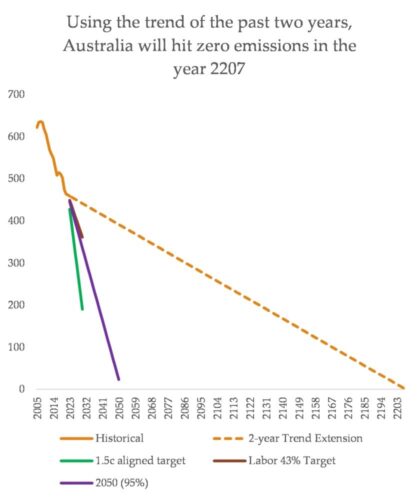

There is a very slight reduction over the past couple of years – but it’s the lowest rate of reductions in recent history. If the trends of the past two years continue, it’ll take until the year 2207 to reach zero emissions.

Land-use data revisions are still completely changing Australia’s climate narrative

It is fundamentally incorrect to mix the emissions relating to the planting and removal of vegetation with the emissions relating to carbon sourced from deep underground. They are not interchangeable, and should be reported separately.

But land-use data are also extremely unreliable, thanks to complex and opaque methodologies using satellite data and other techniques to estimate emissions.

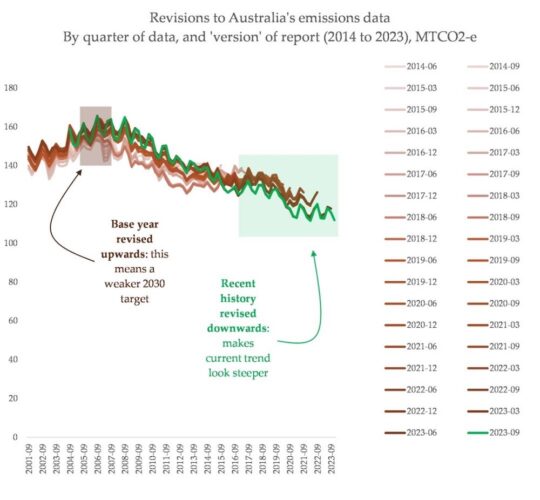

I have compiled every quarterly emissions report since 2014 into a single file, which lets me show below how significant historical revisions to Australia’s land use data are – these changes are on the magnitude of entire other sectors (the data revision from 2022 to 2023, for instance, is the same number of emissions as several major coal-fired power stations):

Australia’s environment department and government blend fossil carbon emissions data with land-use emissions data, and historical revisions have tended to only ever be in a direction that results in a more favourable climate narrative for the government, as you can see for the ‘total’ emissions, which include land-use:

It is pretty noticeable that land-use data is constantly revised in a way that exaggerates climate action, but Australia’s extremely significant coal mine methane underestimation problem remains largely unaddressed.

Recently, Climate Action Tracker brought some welcome attention this problem – highlighting that Australia’s 2030 target – billed at 43% reductions by 2030 – are more like a 24% reduction.

It’s for this reason that I, and others like Greg Jericho , exclude land-use data from charts of Australia’s emissions (in some cases I include it as a separate series, not combined with fossil carbon). And Australia should be setting its climate goals without including this fudge.

Labor’s policy suite isn’t up to the task

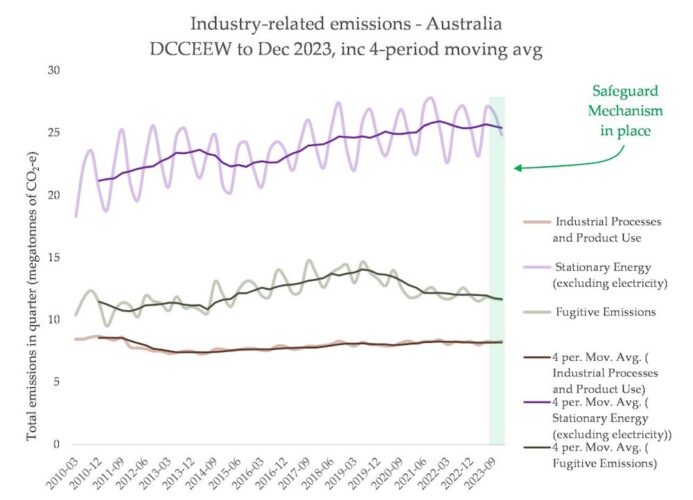

This new data package also shows the first full half-year of the new ‘safeguard mechanism’, a system of mandatory carbon offset purchases for heavy industry and fossil fuel miners above an opaque “cap” in their emissions.

It is going to be a very long time until the data relating to the facilities covered by the scheme is released, but this – as a rough proxy – shows near zero impact so far. Perhaps it’s too soon to judge: which begs the question, when can we judge?

As I’ve written here, even Labor’s own estimates of the climate benefits of its vehicle emissions standards are modest; as are the impacts of its power sector renewables incentives.

It’s not unlikely that Labor glide into the 2025 federal election with almost nothing to show for their climate policies, in the emissions data. While they might plead for patience, climate change is an urgent problem demanding immediate and deep cuts, and we can say with total confidence right now that they’re falling short.