Tuesday was even hotter around the world than Monday, and experts are saying to expect more headlines like this as the northern hemisphere summer rolls on and as the latest El Nino entrenches itself.

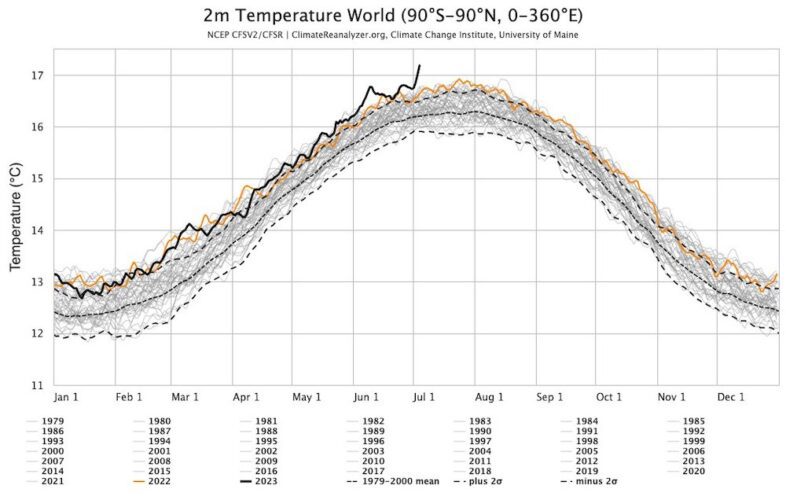

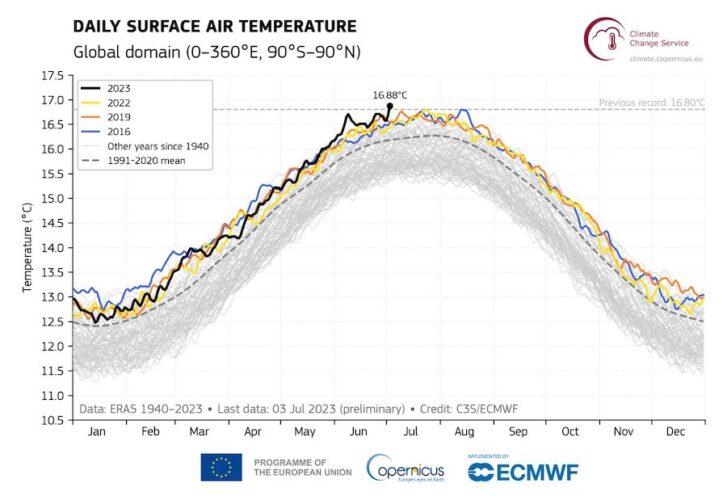

On 4 July global average temperatures taken two metres above the Earth’s surface ticked up again, from 17.01°C the day before to a new record of 17.18°C, according to data from the National Oceanic Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) and compiled by the University of Maine.

It’s possible more warmer days will be seen over the coming six weeks, said Dr Robert Rohde at Berkeley Earth in California on Twitter.

The EU’s Copernicus Climate Change Service also said this week that global average temperatures in June 2023 were 1.46°C above pre-industrial levels.

The Paris Agreement was a commitment by countries to limit warming to an average of 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels.

Global average air temperatures sit between 12°C and just under 17°C during the year, and for the two decades between 1979 and 2000 the start of July averaged 16.2°C.

Sea level temperature spikes

Global sea temperatures have also been higher for longer, with global average temperatures touching 21°C in March and remaining high through May.

Some researchers, like University of Leeds climate physics professor Piers Forste, said a lack of Saharan dust over the ocean and the phase out of sulphur fuels by international shipping to the catalogue of causes.

In 2020, the International Maritime Organisation rules kicked in which phased in low-sulphur fuels for global shipping, a move which resulted in dropping sulphur dioxide emissions by about 10 per cent.

However, some researchers think sulphur particles had been counteracting the effect of greenhouse gas warming and without that extra barrier, warming has increased, adding an extra hurdle to preventing global warming from shooting past 1.5°C.

El Niño fears

The long term drivers are, of course, greenhouse gas emissions, which grew in 2022 by 0.9 per cent to more than 36.8 gigatonnes (Gt) globally, according to the International Energy Agency.

But the current weather is due to a combination of heatwaves in the US, Europe and Canada with the El Niño weather pattern, which the World Meteorological Organisation (WMO) confirmed this week is likely to be on the way.

Climate modelling indicates that El Niño effects such as drought and marine heatwaves will become more intense due to climate change.

El Niño occurs on average every two to seven years, and episodes typically last nine to 12 months. It is a naturally occurring climate pattern associated with warming of the ocean surface temperatures in the central and eastern tropical Pacific Ocean, but in this case it’s also coming at a time of human influenced climate change.

Australia’s Bureau of Meteorology however, is not yet declaring El Niño.

While the WMO gives a 90 per cent chance of El Niño appearing, the BOM’s metrics are showing a 70 per cent chance before summer which is under its threshold for declaring an event is underway.

“El Niño means that there is warmer than average temperatures in the tropical Pacific Ocean and weaker than average easterly trade winds. Because the ocean surface is warmer, more heat is released and the atmosphere warms,” says Ruby Lieber, a PhD Candidate at the ARC Centre of Excellence for Climate Extremes at the University of Melbourne.

“Every El Niño is different and so resulting weather and climate impacts are not certain. In Australia, we would generally expect hotter and drier weather. El Niño increases the risk of drought and bushfires in Australia.”

Although drought is typical of El Niño, the weather doesn’t always play out that way.

In 1979, El Niño brought a wetter year.

Rainfall in Australia is influenced not just by El Niño but also by the Subtropical Ridge, Indian Ocean Dipole and Southern Annular Mode, says Southern Cross University research fellow Dr Abe Gibson.

“Currently, the Indian Ocean Dipole is projected to be in its dry phase while the Southern Annular Mode is negative. Given the slow nature of drought onset, these other influences will all play roles in priming us for, or protecting us from, drought during the transition from winter to spring.”