InterContinental Energy, the Singapore green hydrogen developer that is one of the key players behind the $36 billion Australian Renewable Energy Hub (AREH), has secured more funding from the Singapore sovereign wealth fund and from the world’s biggest green hydrogen investor.

Singaporean fund GIC and Hy24, a joint venture between Europe’s largest private investment house Ardian and FiveT Hydrogen, are kicking in a combined $US115 million ($180 million) to speed up the company’s portfolio of massive green hydrogen projects, two of which are in Australia.

GIC originally bought into InterContinental Energy in April, 2022, and its added commitment comes withs the first by Hy24.

“We launched Hy24 to catalyze the development of the hydrogen industry at scale, by investing in hydrogen leaders and entrepreneurs,” said Hy24 CEO Pierre-Etienne Franc in a statement.

“In the long-term, InterContinental Energy represents this vision and has the most advanced execution plans for large, competitive renewable power basins.”

Four projects, 101 GW of power

The money is to speed up the deployment of InterContinental Energy’s four projects, three of which have a combined generation capacity of 101 gigawatt (GW).

Up to 10 GW of this capacity is supposed to be online by 2030.

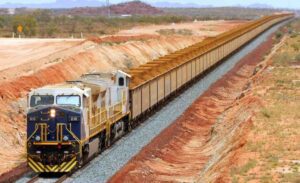

AREH, the 26 GW project in the Pilbara, is possibly the best known. It aims to produce 1.6 million tonnes of green hydrogen annually. Bp bought 40.5 per cent of the project last year, which also counts Australia-based CWP and Macquarie Capital as backers.

InterContinental says this is its most advanced project, which it started in 2015. Land has been granted – 272 hectares in total – in January this year.

InterContinental is also the largest stakeholder in the Western Green Energy Hub (WGEH) in the south-east of the state, another collaboration with CWP but this time also including indigenous nation Mirning Traditional Lands Aboriginal Corporation as a minority shareholder.

That project is proposed to have a capacity of up to 50 GW of wind and solar and produce 3.5 million tonnes per year of green hydrogen.

South Korea is watching this one, with a view to buying any production once it starts.

In July, the Western Green Energy Hub and Korea Electric Power Corporation signed a Memorandum of Understanding for the15,000 square kilometre development.

The company’s other two projects are in the Middle East.

The Green Energy Oman is a 25 GW project with plans to make, eventually, 1.8 million tonnes of green hydrogen a year with partners Shell, the Sultanate of Oman’s energy company OQ, and the renewables investment arm of Kuwait’s sovereign wealth fund, EnerTech.

InterContinental is looking at how a green hydrogen project might work in Saudi Arabia as well.

A long way to go to reach IEA stretch target

In 2021, the International Energy Agency (IEA) said 80 million tonnes of green hydrogen is needed every year to get the world on track for net zero CO2 emissions by 2050.

The world currently has about 600 MW of hydrogen electrolysers in operation, but to meet that IEA target, it needs to grow by 6000 times to 3,670 GW.

How much green hydrogen might actually be produced by 2050 is anyone’s guess: PWC suggests 150 to 500 million tonnes annually, while McKinsey has thrown out 660 million tonnes as a number.

The industry has a very long way to go to reach those kinds of numbers.

In July this year, the IEA said low-emission hydrogen production was less than 1 per cent of total hydrogen production in 2022, or about 950,000 tonnes globally, despite growing 5 per cent compared to 2021.

Asia likely to be the only market for Aussie hydrogen

A think tank in Europe said this week that green hydrogen exports from Australia to Europe are likely to be a non-starter, calling the long-distance shipping of the fuel “expensive and relatively energy-inefficient” compared to piping it in from Norway or Algeria.

Ammonia could be a possible export, but the energy required to crack it into hydrogen at the other end means the use case would need to be right, a Clean Air Task Force spokesperson told the AFR newspaper.

The Clean Air Task Force suggested in its report that Australia should look to Singapore, Japan and Korea to achieve its aim of being a green hydrogen superpower, and not to much more distant Europe — despite tentative plans with Germany.