Climate change has clearly been a major pivot point in the recent federal election. The issue was on the minds of voters for some time, as polling over the past few years kept showing, but more so it seems, after the past two years.

Australians were eager to see action on climate even before the 2019 election. However, this time we had bushfires and floods in quick succession, and little meaningful progress on climate and energy policy.

Is this the tipping point people have been waiting for? Do Australians finally accept the climate science and agree we need urgent and rapid decarbonisation?

More than net zero by 2050, the science tells us we need 50% reduction from 2020 to 2030. This year’s election results show Australians have heard this and are eager for fast action.

So, how are we going to achieve these targets?

First, we’d ideally adopt a cap-and-trade scheme that policymakers in Europe have accepted and have been strengthening since 2008. The key objective here is accelerated and orderly retirement of coal plants, starting with those that are most inefficient and polluting.

However, if politics makes this difficult, the safeguard mechanisms can be strengthened and turned into a strong baseline and trade scheme, which would be ideal.

Second, a comprehensive review of the National Energy Market frameworks is needed – one much stronger than the current market reform proposals from the Energy Security Board (ESB).

The ESB’s objectives of modifying the current National Electricity Rules are necessary as an interim measure to ensure the market rules appropriately track the emerging technologies.

However, it’s clear that key elements of the market design (both wholesale energy trading and network regulation aspects) are no longer fit for purpose, as they were designed for an era of fossil fuel generation, and not for energy resources produced by consumers or for electric vehicles.

We need to go back to the drawing board and redesign, from the ground up, a market regulator that’s focused on renewable technologies and storage for a 100% renewables system.

This has to happen quickly so that the pathway to the end state of the market design is clear, and allows the ESB and others to make orderly transformations.

Third, a dramatic step up in the electrification of the transport sector is required, with an incentive policy needed to transition to only new electric vehicles (or other zero-emission transport technologies) sales by 2030.

There are hardly any policies at the state or federal level to improve vehicle efficiency and reduce transport-related emissions, and Australia has among the most inefficient and carbon-intensive vehicle fleets in the developed world.

Fourth, investment is needed in both research and development of emerging technologies and the uptake of these new technologies in the energy industry.

This is to allow energy generation and retail companies, as well as distribution and transmission network operators, to seriously redirect funds to investing in new business models and new technologies, and in more university research, particularly into the integration of large amounts of inverter-based resources (wind, solar, batteries) into a grid designed and operated for synchronous generators.

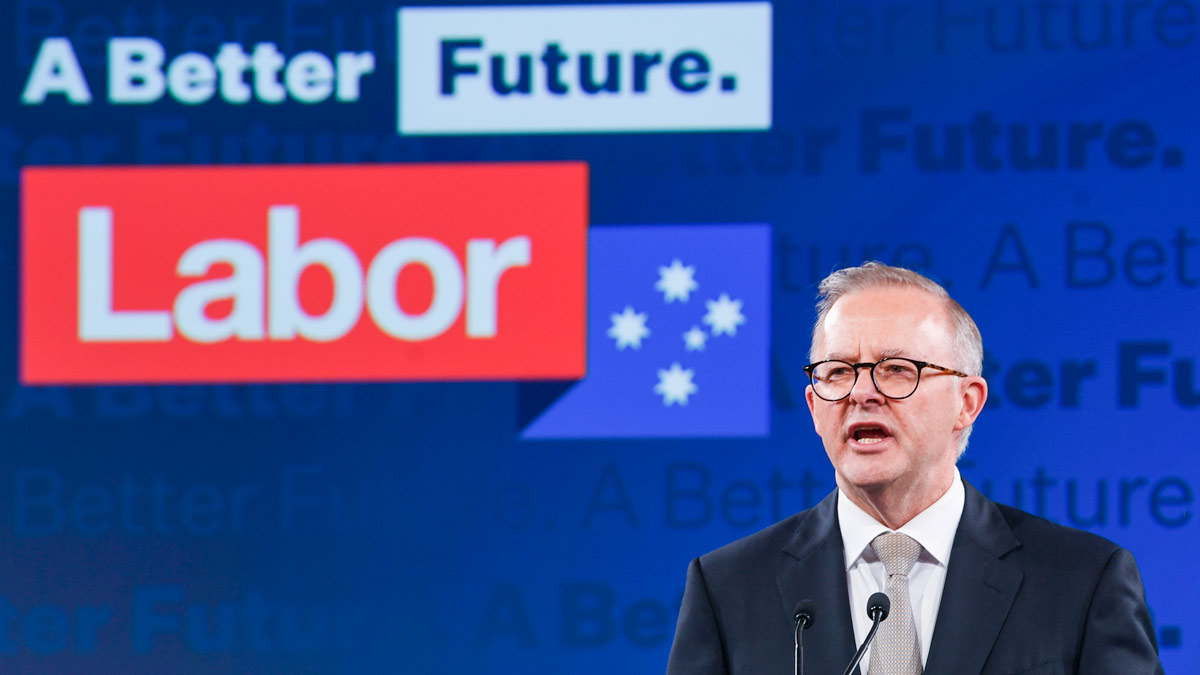

PM’s positive start

Our new prime minister has already been making positive moves.

A more ambitious carbon emission abatement target is very welcome, as is strong investment in new electricity transmission, as these are essential to allow the transition to a low-carbon energy sector. However, these policy changes don’t go far enough.

Australia leads the world in the integration of wind and solar energy into a continental-scale grid. And we’ll face grid integration challenges that no country globally has previously faced.

There should be a stronger focus on accelerating research and development domestically, as we can’t buy this as consulting services or off-the-shelf technology overseas.

We really are at the bleeding edge, and Australia has the capability to do this. We just need the investment in our future now.

Ariel Liebman is director of the Monash Energy Institute and Professor of Sustainable Energy, Faculty of IT

Roger Dargaville is deputy director of the Monash Energy Institute, Resources Engineering, Faculty of Engineering

This article was originally published on Monash University’s Lens blog. Republished here with permission