Under-Leveraged Best Practices for Scaling Productive Use of Energy Appliances: Part 1 — Sales Support and Market Access

In the wake of growing global solar home systems uptake, Productive Use of Energy (PUE) appliances — i.e., energy-powered and income-generating devices — have received increased attention due to their multiple socio-economic benefits. They can not only increase revenue for low-income populations and mitigate climate change effects, but also improve global energy access.

Although traditional solar appliances such as lanterns, fans or TVs can also be transformative for microenterprises, attracting more customers and increasing revenue, the impact of PUE appliances extends to the customer. The term “productive use” refers to technologies resulting in the direct production of goods or provision of services. It encompasses many appliances, from solar mills to egg incubators and walk-in cold rooms. In this article, we will focus on the two PUE appliances with the most mature and promising markets, solar water pumps (SWPs) and solar refrigerators.

The positive impact of these two types of appliances on livelihoods is multi-faceted. Farmers irrigating their crops with an SWP can increase yields by 50-400% (compared to rain-fed crops), while boosting their income by 100-350%. Similarly, solar refrigerators can increase income for fast-moving consumer goods shops and pharmacies and improve end-consumers’ access to essential products like medicine, vaccines or simply fresh food. Both appliances could also be game-changers in the path to food security, as SWPs can increase resilience against climate disasters, and solar refrigerators can significantly reduce food waste.

Despite all these potential benefits, the market for PUE appliances is still nascent, with less than $100 million raised and less than 100,000 SWPs and 50,000 solar refrigerators sold globally since market launch — compared to 9.5 million traditional solar energy kits sold in 2022 alone. Only a handful of big players have sold a couple of thousand units or more — e.g., SunCulture, Futurepump and Davis & Shirtliff for SWPs, Koolboks, SureChill and Promethean Power Systems for solar refrigerators.

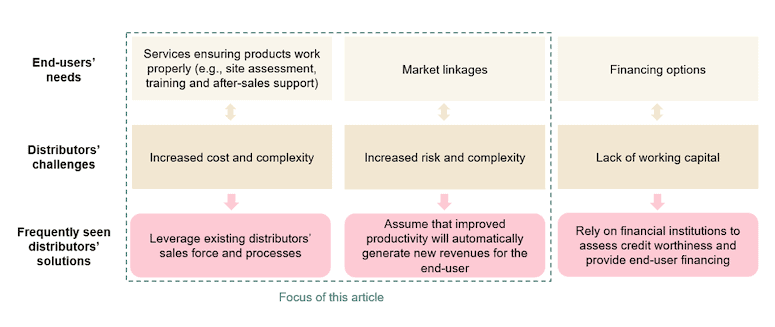

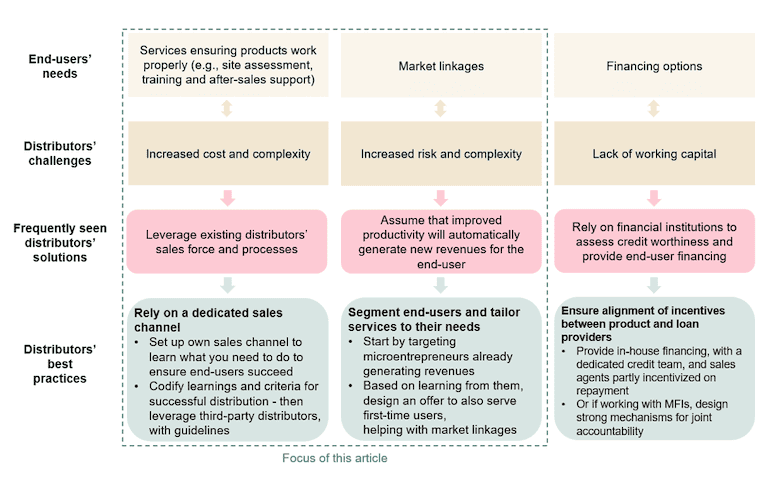

This slow uptake can be explained by the relatively smaller market for these products compared to domestic appliances, combined with the necessity for companies to build a holistic offer to ensure that the end-user succeeds in generating income, which translates into complex, seemingly risky business models. Indeed, all PUE end-users require in-depth training and after-sales support to properly use these complex products, and most of them need market linkages to generate revenue, and financing options to purchase the appliance. To meet these needs, PUE distributors are facing three challenges that have already been well documented:

- Providing in-depth assessment of the end-users’ situation, extensive training (of both end-users and sales agents), and after-sales support increases the cost and complexity of their business model;

- Guaranteeing market linkages to end-users is a big additional lift for PUE distributors, as it increases risk and complexity;

- Offering financing options to end-users requires high levels of working capital and financing skills that distributors typically lack.

What has received less attention is how to overcome those challenges, resulting in some persistent myths that are pushing manufacturers and distributors to make suboptimal choices. This article will look into these common pitfalls, and share best practices which have the potential to sustainably address the first two challenges listed above. The third challenge, offering end-user financing solutions, will be discussed in the second article of this series.

The Distribution Challenge for PUE Appliances

PUE appliances are complex products to sell. As new and technical products, end-users are either unaware of or understandably sceptical about their benefits. All companies selling PUE appliances have realized that simply putting them in retail shops is not sufficient to sell these devices, and that these complex products need direct interactions — and ideally demonstrations — to convince customers to purchase them. Additionally, end-users will rightly demand after-sales service to ensure that they can fully benefit from their PUE appliance.

While leveraging existing distributors with assumed synergies is a tempting way to overcome this complexity, existing trials have shown few successes. For instance, Solar Sisters, a last-mile distributor of energy products in Kenya, piloted the inclusion of PUE appliances in its product portfolio. The company quickly realized it could not rely on existing sales agents to provide efficient after-sales support. Similarly, solar refrigerator brands have tried to leverage third-party distribution networks offering synergistic products, such as soft drinks distributors. However, these distributors’ agents must first achieve their (drinks) sales targets, which they do by visiting a high number of retail outlets a day. They do not have time to explain a new complex product such as a solar refrigerator, and are wary of jeopardizing their good relationships with these retailers if they push an expensive product too hard. As a result, sales via this channel have proven to be extremely low.

To sell complex products such as PUE appliances successfully, a specialized sales channel is required — i.e., trained, dedicated, close-to-full time sales agents, who don’t have conflicting sales targets for other products, and who are supported by tailored processes. SunCulture, the market leader for SWPs in sub-Saharan Africa (with over 45,000 pumps sold to date), is fully integrated and focuses on selling SWPs only. Meanwhile Bonergie — a distributor of Lorentz’s SWPs in Senegal — runs its irrigation activities via a dedicated department. Both companies have specialized sales agents, incentivized purely on their SWP activity, who efficiently train end-users and provide reactive after-sales support, leading to high satisfaction and repayment rates. Both also have dedicated support processes for this activity.

Existing distributors can still play a role in selling PUE products, if they are ready to invest in setting up a dedicated department. PUE appliance brands can support them in doing so, ideally once they have learned the ropes themselves. But these partnerships between brands and existing distributors should be carefully designed, with clear roles and responsibilities, depending on the third-party distributor’s assets and constraints.

For instance, some companies — such as Koolboks, which sells solar freezers — are first developing their own sales agent networks, enabling them to learn first-hand what it takes for their clients to succeed. In Koolboks case, they are waiting until they have raised their Net Promoter Score — a common metric for measuring customer satisfaction and loyalty — sufficiently, proving that their processes are sound, before starting to design partnerships with others for expansion. SureChill, a company that sells solar refrigerators in several African countries, has found that its distributors have very wide-ranging levels of performance, with the best ones being those who have dedicated agents for these new products. Similarly, existing solar home system distributors that are diversifying into these new product lines are now creating parallel, dedicated sales agent networks — if not fully new departments in charge of this new offer — to successfully distribute those products.

Another model that has proven successful involves leveraging specialized distribution networks that are selling similar (not just synergistic) products and are ready to carry a broader range of products. This is only possible in relatively mature markets where there are existing distribution networks for traditional (non-PUE) appliances, such as agriculture-appliance shops, that are interested in taking up this new product. The PUE brand then needs to build an appropriate training process, ideally validated with a certification, to ensure that the distributor can do a proper business case assessment and offer end-user training. For example, Davis & Shirtliff, the leading supplier of water-related equipment in the East African region, decided to use its dense network of 1,500 irrigation resellers to offer SWPs to farmers throughout Kenya. The company trains and certifies all these resellers through an online platform — which also covers basic agricultural concepts to help them explain the pumps’ functions and value to farmers — and provides them with a mobile application to facilitate site visits and help size their irrigation needs.

In any case, PUE appliance distributors should make sure they follow best practices in selling complex products in low-income markets. This includes helping potential clients assess how much they could earn from purchasing the PUE appliance, providing impeccable after-sales service, incentivizing sales agents not just on sales but also on end-user satisfaction and repayments, leveraging satisfied clients as referrals for new sales, and building the required infrastructure to maximize the chances that clients will truly benefit from these products. Only then will end-users — and PUE distributors — succeed.

The Market Access Challenge for PUE Appliances

Convinced of the benefits of PUE appliances, distributors often assume that all end-users who purchase their products will succeed, even those who have not used any alternative devices before — e.g., farmers who have never irrigated their crops, or small shops that have never sold chilled products. However, PUE appliances are expensive, with monthly repayments often larger than the customer’s mean non-food household expenditures. If end-users are not able to generate additional savings or revenues, they will surely default. And indeed, many distributors selling PUE appliances on credit have reported high defaults due to end-users being unable to reap the full product benefits, as they lacked market demand, access to potential suppliers or customers, and/or knowledge of market prices.

As providing market linkages is complicated, younger PUE distributors can start by targeting only microentrepreneurs who are already generating revenues, who will definitely save or earn more thanks to the PUE appliance. For example, Bonergie is targeting diesel pump users who will save on fuel by using solar. This is an attractive value proposition for farmers, as demonstrated by KickStart, a provider of entry-level manual pumps, which has seen many of its clients switch to an SWP once they have understood the benefits of irrigation and built market linkages. Similarly, solar refrigerator companies could first target retailers or pharmacies that were previously running refrigerators on a diesel generator or purchasing ice to keep their products cool. These end-users already have suppliers of products that benefit from a cold chain, and customers for their cold products, and will automatically gain from their purchase by saving money on fuel.

By learning from these first clients about their suppliers or buyers — e.g., what types of products they are selling thanks to the PUE appliance, who their customers are, etc. — along with any other information that has helped them become successful entrepreneurs, PUE distributors can develop a blueprint for how to build a holistic offer, including market linkages. This will allow them to serve first-time users, who have never generated income before with an alternative technology.

Some PUE distributors take this support a step further, providing direct market access to their clients. For instance, Promethean Power Systems, a company that designs and manufactures refrigeration systems for cold-storage and milk chilling applications, purchases the milk collected by village-level entrepreneurs through chilling hubs installed in strategic locations. Others have opted instead to play a simple match-making role, reducing the operational complexity compared to fully integrated market access. For example, Wala — a company that sells various PUE appliances to farmers — is connecting farmers who purchased an SWP to off-takers in the soya bean value chain. And SunCulture has started to build partnerships with off-takers, planning to leverage its mobile application as a platform to match them with farmers.

Service models, in which companies are offering PUE appliance services for a fee, often include these market linkages. For instance, Stable Foods — a Kenyan company providing irrigation-as-a-service via fixed, high-capacity SWPs that serve groups of farmers — offers crop purchases at a guaranteed minimum price, to be sold in the shops owned by the company. Thanks to this embedded market access, the farmers are sure to multiply their revenue by at least two to three-fold in one season. Similarly, Soko Fresh, a company offering solar cold storage units for rent in Kenya, is using its network of off-takers to guarantee higher prices to its cooling-as-a-service farmer clients. These service companies need to carefully choose the locations of their larger-scale PUE appliances, to secure a high enough customer density — and therefore utilisation rate — to be commercially viable.

As these approaches illustrate, PUE companies can achieve greater long-term growth by setting up their own sales channel in a small area and targeting microentrepreneurs who are already generating revenues, then meeting these end-users’ key needs. In the second article of this series, we will explore how to sustainably address the third challenge facing PUE companies: how to handle the high-level of working capital and financing skills required to offer financing options to end-users.

This article is the first of a two-part series written by Hystra in collaboration with the Global Distributors Collective and with the support of British International Investment‘s technical assistance facility, BII Plus. Read the second article here.

Part of this article is based on our research with our partner ISF Advisors, on the current state and future potential of small-scale irrigation: Access the full report here. This report was funded by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation. The opinions and findings expressed within are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views, strategy or funding priorities of the Foundation.

Thomas Charoy is a consultant at Hystra; Lucie Klarsfeld McGrath is a Partner at Hystra and co-founder of the Global Distributors Collective.

Photo credit: Nabin Baral / IWMI

- Categories

- Agriculture, Energy, Environment, Technology