How Does Regenerative Agriculture Work?

Shifting the Focus to Soil Health and Sustainability Can Bring Environmental, Economic, and Social Benefits

This article by Heeseung Kim, Maya Fischhoff, and Abby Litchfield is part of “The Basics” series by the Network for Business Sustainability (NBS) that provides essential knowledge about core business sustainability topics.

What if there were a better way of farming? A way that improved the soil, addressed climate change, and could be more profitable too. And what if this method of farming had a successful track record, tested by time all over the world?

This method is called “regenerative agriculture.” While the phrase was popularized in the 1980s, the concepts of regenerative agriculture were practiced for centuries before it got its current name.

It’s important because today, most agriculture has taken a different path toward “industrial” agriculture: large-scale, intensive production. These operations are contributing to problems like climate change, biodiversity loss, and even the declining nutritional value of food. For example, agriculture accounts for roughly 25% of global greenhouse gas emissions.

If you’re in a business that sources from agricultural suppliers, prioritizing regenerative agriculture can help you meet sustainability goals. If you’re a farmer, these ideas relate directly to you.

Everyone can play a role to help regenerative agriculture meet its full potential. Right now, regenerative agriculture is working powerfully at a small scale, but more is needed for it to spread.

This article describes:

- The goals and practices of regenerative agriculture.

- Its value from a sustainability and business perspective.

- How to get involved.

Let’s dig in.

What Is Regenerative Agriculture?

The “regenerative” concept has been growing in popularity over the last few years. That’s not because we needed another buzzword. It’s because it can take “sustainability” to the next level.

Sustainable processes can be sustained in the long term: They meet today’s needs without compromising the ability of future generations to do the same. Regenerative processes aim to improve the systems they operate in.

Here’s how this applies to agriculture:

Regenerative agriculture is a way of farming that seeks to actively improve the health of the environment as opposed to simply maintaining it (or worse, degrading it). It’s not a single standard or certification; it’s a collection of farm management practices. At the core is an emphasis on soil health.

Soil — dirt — may not be glamorous. But it’s the foundation of agriculture. Healthy soil stores essential nutrients, like carbon and phosphorus. It’s part of “nutrient cycling” processes, which are critical for healthy foods and ecosystems. Essentially, animals and plants take nutrients in from the soil and air. When those plants and animals die and decompose, the nutrients release back into the environment, including the soil.

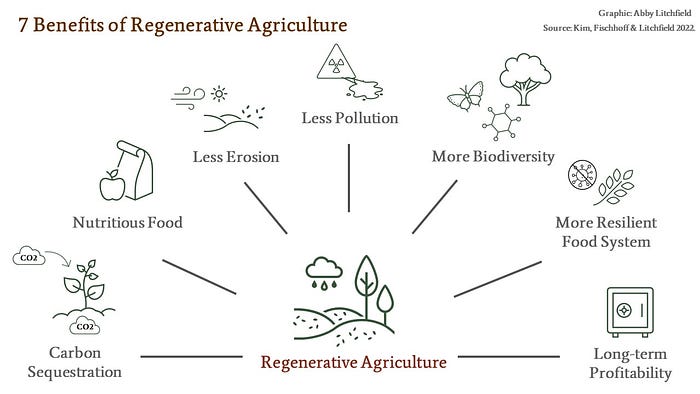

Healthy soil and regenerative practices create benefits from biodiversity to cleaner water to healthier workers and more productive land.

Comparing Regenerative and Industrial Agriculture

Industrial agriculture doesn’t have the same focus on soil health. Instead, it emphasizes yield and efficiency to maximize immediate profits.

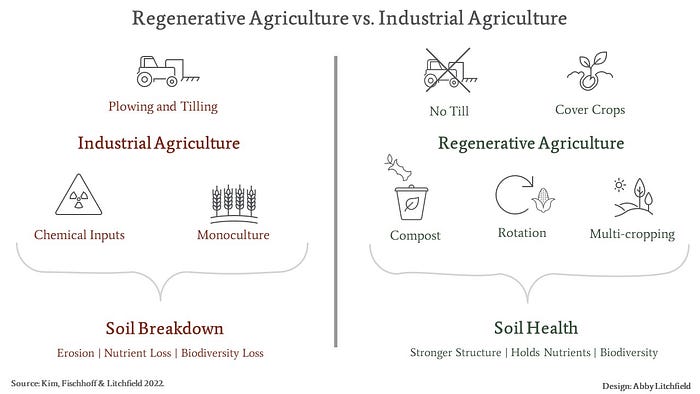

Practices like plowing, chemical applications, and monocultures can provide short-term returns and the large-scale production expected in today’s agricultural supply chain. But over time, they break down the soil and lead to less resilient ecosystems.

The result is a dramatic loss of healthy soil, widespread runoff and pollution, and a crisis in biodiversity. There’s concern about inequality, with industrial agriculture favouring large farms. And, in the face of climate change, agriculture is both vulnerable and a contributor.

“There was a time when industrial agriculture seemed to be a panacea for a fast-growing world,” notes a report from the United Nations Environmental Programme. “But not everything went as anticipated. Decades of industrial farming have taken a heavy toll on the environment and raised some serious concerns about the future of food production.”

In this setting, regenerative agriculture is increasingly hailed by a wide array of sectors: from small farmers to large corporations to government agencies and nonprofits.

If you’re interested in the agricultural space, you likely know of other alternative agriculture approaches, from organic to permaculture. These relate to regenerative agriculture because they all emphasize a system that is naturally self-sustaining, explains Dr. Deishin Lee, a professor at Ivey Business School. Growing food should be renewable or naturally replenished. Needing to constantly add external inputs is a sign that something is broken.

Different sustainability-oriented terms are all a way of returning to that self-sustaining system, says Lee. The more you grow, the more you are able to grow — and without adding external chemical inputs.

Here’s what regenerative and industrial systems look like on the ground, and what they produce.

Industrial Agriculture Practices

With industrial agriculture, plowing and tilling churn the soil. That breaks up the soil structure, which interrupts natural processes like carbon sequestration and makes the soil less nutrient-rich for crops. It also enables soil erosion from wind and water. Monocultures — a single crop — also drain the soil of specific nutrients.

Farmers add synthetic fertilizer and pesticides, in part because overworked soil doesn’t capture nutrients as well. These inputs can be costly, harmful to workers, and polluting. Fertilizer and pesticides can contaminate groundwater or run off into nearby waters, causing algae blooms and fish die-offs.

Planting only one species over a large land area discourages plants, animals, and insects from living there. As biodiversity declines around the globe, agricultural areas could be an important refuge.

Regenerative Agriculture Practices

With regenerative agriculture, “no till” or “reduced till” mean that seeds are planted through what’s left of the previous season’s crop. Soil structure remains largely intact. Cover crops are also grown, primarily to benefit the soil. These help reduce erosion and capture nutrients in the soil.

Rotating crops with different nutrient needs gives the soil time to recover; rotating animals between different grazing areas is similarly beneficial. Multi-cropping, or integrating animal species with crops and trees, can fertilize the soil and keep down pests.

There’s less need for chemical fertilizer or pesticide. Compost is commonly used: Combining food waste, manure, and plant residue for an ultra-rich material that recharges soil.

Regenerative agriculture supports biodiversity at all scales. Healthy soil is full of microorganisms. Conservation buffers, a common regenerative practice, create permanent vegetation around crops or streams.

Regenerative Agriculture and Climate Change

As climate change draws more attention, regenerative agriculture is seen as part of the solution. That’s because it can help with both climate mitigation and adaptation.

In adaptation, farming becomes more resilient in the face of climate change. Healthy soil absorbs more water, making farms better able to withstand both flooding and drought, and reducing runoff. Diversified crops make the risk of one total failure less likely.

Mitigation is about reducing the amount of carbon in the atmosphere. Regenerative agriculture causes fewer emissions, because there’s less machinery use and fewer chemical inputs. It’s also better at sequestering carbon. Plants remove carbon from the atmosphere and release it into the soil. Healthy, undisturbed soil is better able to “sequester” or store that carbon and prevent it from warming the planet.

Views differ on how much carbon regenerative agriculture can sequester. For example, one study shows regenerative agriculture leading to a 5.3% increase in soil carbon stocks after 10 years. But an analysis by the World Resources Institute is more skeptical, in part calling for additional research. “Soils naturally store massive amounts of carbon, and the scientific understanding behind this process is still emerging,” their report states.

The Business Case for Regenerative Agriculture

Regenerative agriculture has tremendous potential to create a better world. And it can be profitable. But the business case is still complicated. The picture looks different in the short- and long-term, and for small and large farms.

Regenerative Agriculture Can Pay Off Over Time

Moving from conventional to regenerative farming requires an upfront investment of money and education. Some regenerative practices (like cover-cropping) take a few seasons to develop soil health and improve the yield of revenue-generating crops. Others (like multi-cropping with animals) can require more active management and more staff time.

Over the long term, there are many examples of regenerative agriculture providing higher yields and/or higher profits than industrial agriculture. Case studies in many countries show these improvements, notes Network for Business Sustainability Director Jury Gualandris, who studies regenerative agriculture. But the data don’t yet provide an absolute answer on financial returns, he says.

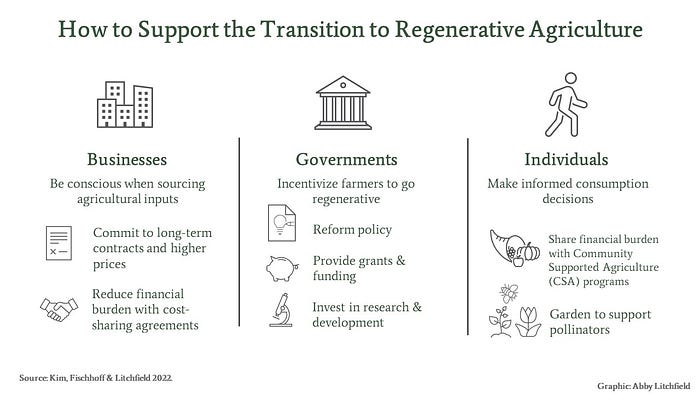

Because regenerative agriculture is so good for the land and community, more people should support its adoption, says Gualandris. “Regenerative agriculture will continue to struggle financially if businesses, governments, and consumers don’t reward its positive contribution.”

Regenerative Agriculture Is Currently Easier at Small Scale

For small farms, regenerative agriculture is generally an easier sell. There are many examples of successful small-scale regenerative farms. These usually focus on high-quality products for markets willing to pay a “green premium” — for example, local restaurants or boutique grocery stores.

At a larger scale, regenerative agriculture is more difficult — in part because of the match with our food supply chain. Existing supply chains seek efficiency and standardization. They’re set up to process huge quantities of a specific product, on a specific schedule.

Regenerative agriculture, with intercropping and multi-cropping, is less specialized. “Regenerative agriculture is high variety, low volume, whereas industrial agriculture is low variety, high volume,” says Gualandris. Supply chains aren’t yet set up for that kind of sourcing diversity.

Support the Transition to Regenerative Agriculture

Regenerative agriculture is taking hold — but it has a way to go. Here are ways for everyone to help.

Businesses that buy from farmers can support the transition by committing to long-term contracts or entering cost-sharing agreements to alleviate farmers’ financial burdens. That can mean paying higher prices. Here are some examples of such support:

- Food company General Mills has been working directly with farmers to understand region- and crop-specific challenges to regenerative agriculture, and hosting educational workshops to share solutions across their supply chain. That supports their goal to deploy regenerative practices across one million acres of land by 2030.

- French clothing company Kering has founded a Regenerative Fund for Nature, which is an investment fund that “will provide grants to farming groups, project leaders, NGOs and other stakeholders who are ready to test, prove and scale regenerative practices.”

Governments can incentivize farmers to implement regenerative practices. This can happen through policy reform (such as Canada’s plan to reduce fertilizer emissions), funding (like the U.S.’s cost-sharing conservation program), and increased research and infrastructure to support regenerative systems.

Individuals can purchase food from local farms that are using regenerative principles. You might find one at a nearby farmer’s market, or through a Community Supported Agriculture program, which helps share some of the farmers’ economic burden. Keep an eye out for broader certifications, as well: They’re on the way!

Regenerative Agriculture — Time-Tested and Future-Oriented

Regenerative practices draw on thousands of years of knowledge. Indigenous peoples have used many of these approaches across the world. Over time, they’ve adapted and improved them.

For example: Indigenous peoples in Central and North America grew corn, beans, and squash (the “three sisters”) together. In this “multi-cropping,” each plant served a purpose. Corn stalks were poles for the beans to grow up. Beans fixed nitrogen in the soil, reducing the need for fertilizer. Meanwhile, large squash leaves created cool microclimates close to the ground, keeping the soil moist and free of weeds. This system led to highly productive crops and a high-quality diet.

“Indigenous peoples have effectively used the ecological relationships among various plant and animal species to create food systems that symbiotically nourish humans and the environment,” says Lee. “By learning and understanding the practices of Indigenous peoples, we can enable wider adoption of sustainable agriculture.”

This article was originally published by the Network for Business Sustainability. B The Change gathers and shares the voices from within the movement of people using business as a force for good and the community of Certified B Corporations. The opinions expressed do not necessarily reflect those of the nonprofit B Lab.