This past month’s extreme flooding in Kenya, heatwave in West Africa and drought in Southern Africa reveal a continent on the frontlines of climate change. Such increasingly intense and frequent weather events are exacerbating Africa’s $200 billion annual sustainable development finance gap.

A promising trend: African institutional investors’ growing interest in impact investments, and infrastructure and small business finance investing in particular.

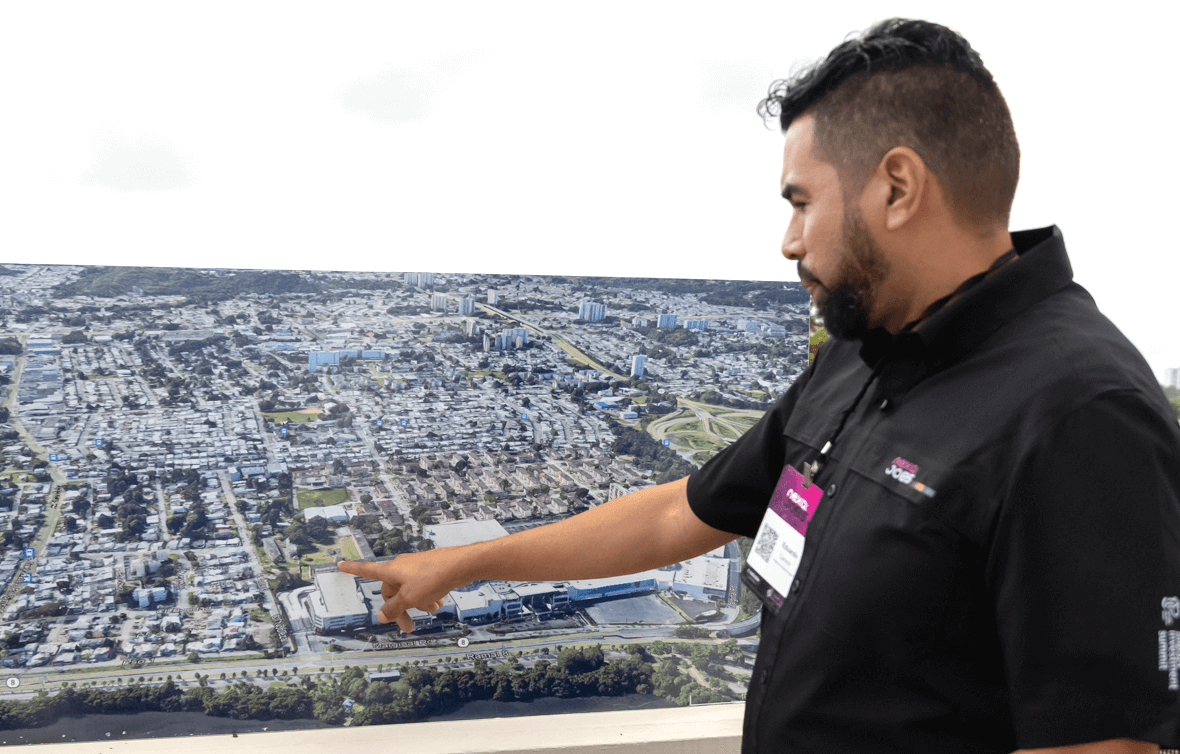

In Nigeria, local insurance companies and pension funds, as well as impact investors, are channeling capital to infrastructure and economic stabilization funds managed by the Nigeria Sovereign Investment Authority, which manages Nigeria’s $2.5 billion sovereign wealth fund. Local institutional investors “understand the impact of what large scale investment can do and want to partner with teams on the ground to deliver that,” said NSIA’s Aminu Umar-Sadiq at the African Private Capital Association’s annual conference in Johannesburg last week.

Africa’s pension funds and insurance companies have historically shied away from infrastructure, private equity and other niche assets classes, favoring bond markets and listed equities. There has been a noticeable shift in recent years of the types of investors backing African infrastructure funds in particular.

“What was paramount in terms of the type of financing was senior debt, mainly from development finance institutions,” observed Rachel More-Oshodi of Nigeria-based fund manager ARM-Harith Infrastructure Investment. “Later on, commercial banks started to get comfortable with the risk allocation, but very few [investors] were providing equity and so it remains sort of senior debt type of play.”

The firm is a long-term infrastructure equity investor and also provides critical project development capital to help projects become investment ready. ARM-Harith last year launched its ARM-Harith Cities and Climate Transition Fund. The planned $250 million fund, incubated at the Global Innovation Lab for Climate Finance, aims to “mobilize international capital and domestic pension savings into infrastructure that supports a low-carbon future.”

To coax more African institutional participation into new opportunities, NSIA is planning to launch a new blended-finance fund that will leverage philanthropic capital to derisk earlier-stage investments for local pensions and insurance companies, said NSIA’s Umar-Sadiq.

Unlocking liquidity

Slow but steady progress in unlocking new pools of investment capital is pressuring Africa’s sustainable investing community to find new ways to free up existing pools.

Lack of data and examples on exits has deterred private equity investors from engaging in Africa. Paris-based Amethis, which invests in Africa, focuses only on sectors where there is existing liquidity, like financial services and fast-moving consumer goods.

The small secondaries market in Africa “creates a perception for any investor looking at the market that they won’t have options when it comes to how their value comes out,” observed John Owers of British International Investment.

BII is among a small group of investors working to create clearer exit pathways to usher more private investment into the region. The UK development finance institution earlier this year sold its long-held stakes in three impact funds to BlueEarth Capital as part of a new strategy to seed a secondaries market in Africa and other emerging markets.

At the AVCA summit, Owers issued a call to action for other “buyers who have a clear strategic interest in doing this.”

On the debt side, the high-interest, inflationary environment places urgency on unlocking small business finance, said Zain Latiff of small business private lender TLG Capital.

“It’s crucial to reassess traditional investment strategies,” he said, adding, “The answer to the liquidity problem lies with the banks.”

TLG engages banks during its investment process to educate them on its portfolio and businesses’ growth trajectories and financing needs.

“The bank is fully involved in that process, so that when we exit in three, five or seven years, there are natural exit routes,” Latiff said.