There was a clear political message from the new Labor government when releasing parts of the state’s Network Infrastructure Strategy – the roadmap for the transition from coal to renewables – to journalists on Wednesday.

The first was that this was costly, and it was going to be late, running over previous timelines. The inference, even if not stated explicitly, was that shutting coal fired generators, including the biggest in the country at Eraring, on current timelines was going to be tough.

What other choice did the state government have, energy and climate minister Penny Sharpe suggested, when things are going pear-shaped and the priority must be keeping the lights on. And, the media was told, it was the fault of the previous government and its privatisation strategy that it was turning out that way.

What was alarming about that briefing and the political message that went with it is that it just a partial picture of what is included in the actual roadmap prepared by EnergyCo.

The Network Infrastructure Strategy is a particularly interesting document, a 20-year blueprint for the future similar in scope to the AEMO Integrated System Plan, and which actually presents three main scenarios, including a complete coal exit by 2030.

This latter scenario – of which no mention was made in the media briefing – is particularly interesting because it is the only one that accords with a 1.5°C scenario, and probably the only one that is consistent with the realities facing the owners of the state’s ageing and increasingly unreliable coal generators.

The central scenario presented by the government has four coal generators closing by 2033, but one plant – Mt Piper – still burning coal in the state in 2039.

The Coal Exit by 2030 and Strong Electrification scenario has all the coal generators gone by the end of the decade, and it models big increases in demand in the move away from fossil fuel use in the home and industry, and the uptake of green hydrogen.

“The Coal Exit by 2030 and Strong Electrification (is) a single scenario in which all coal-fired power stations in NSW close by 2030, earlier than currently anticipated, with transport, industry, households switching to electricity, and new hydrogen electrolysers adding to demand,” the document says.

The difference between the two comes in the scale of the REZs, and the transmission capacity that they can carry. The Central West Orana zone, for instance, could be upgraded from the planned 4.5GW to more than 10GW, to support the electrification and any renewable hydrogen growth.

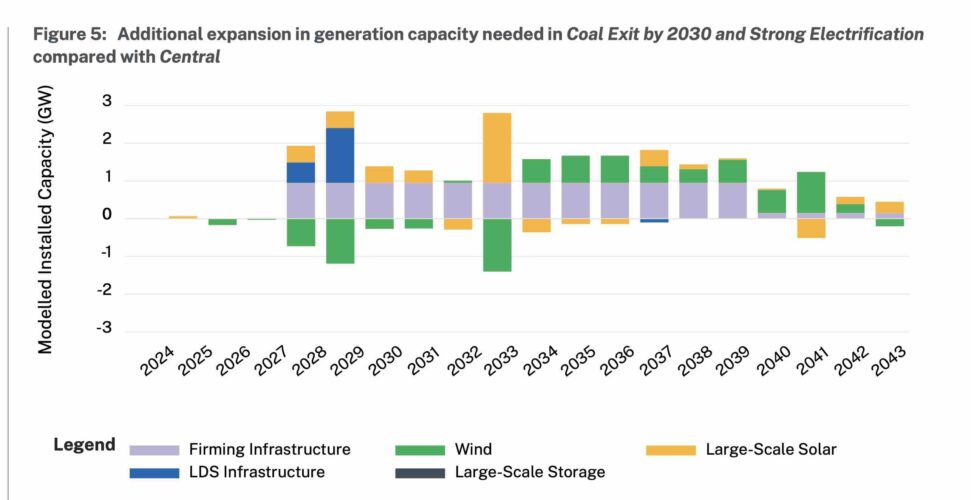

The changes in investment in new generation and firming and storage capacity is represented in this graph below. Those above the line show increases, while those below show decrease.

It is clear that an early coal exit will require a greater focus on firming and long duration storage, and less on wind, according to the EnergyCo analysis.

What’s interesting is that the analysis makes clear that the central, and particularly the transmission delay scenarios, will result on greater reliance on expensive gas generation, and less capacity for more renewables.

“This would take the form of higher cost technologies such as gas generation, potentially increasing electricity prices for NSW consumers,” the document warns. “The timely delivery of network infrastructure would protect against this by allowing low-cost renewable energy to connect.”

When the Liberal government lost power in March RenewEconomy wrote that the country had lost its best energy minister, Matt Kean, and expressed its hope that the new Labor government would not trash its legacy.

The NSW transition is hugely ambitious – get ready for the quick exit of all the coal generators in the country’s most coal dependent state, and make sure enough renewables and storage are in place to fill the gap. The fact that it does have bipartisan support speak to the realities of its ageing coal fleet.

It’s transition at a scale beyond that contemplated by other states, although Western Australia has (surprisingly) emerged with a hugely ambitious plan that takes into account the massive surge in demand from electrification and green industry.

Sharpe, to her credit, has been trying to say the right things, that the roadmap has bipartisan support, and that it should be “accelerated”, but she and the rest of the government remain equivocal about the future of Eraring, in particular.

But the handling of this report underlines real questions about the government’s ability and willingness to push harder, and make the transition at the speed required. To upgrade the Central West Orana REZ, for instance, requires a political decision.

What the industry needs now is less hedging of bets and a clear message from the government that it’s intention is to the right thing and decarbonise at the greatest speed. We’ve yet to see it. It’s time to press the bright green button.